Assessing Executive Function Skills | Tasks & Batteries

Executive functioning skills are a set of mental and cognitive processes that facilitate individuals to control and monitor their own behavior and ultimately achieve their goals. There are specific tasks and comprehensive batteries that enable researchers to evaluate these skills.

What are Executive Function Skills?

Executive function (EF) is oftentimes described as the “control center” of the brain and is used as an umbrella term for a variety of cognitive processes that help an individual to coordinate different skills required for the initiation, planning, and control of goal-directed behavior (Reimers, 2019).

Executive functioning skills are practical skills or abilities that arise from the executive function. The three commonly studied executive functioning skills are:

- Inhibition: The suppression of unwanted responses and distracting information.

- Shifting: It is the switching between different tasks.

- Working memory: Monitoring and manipulating information in mind (Cragg, 2014).

Tasks for Asessing Executive Function

Executive functioning tasks are individual tests designed to assess specific skills within executive functioning, such as working memory or inhibition.

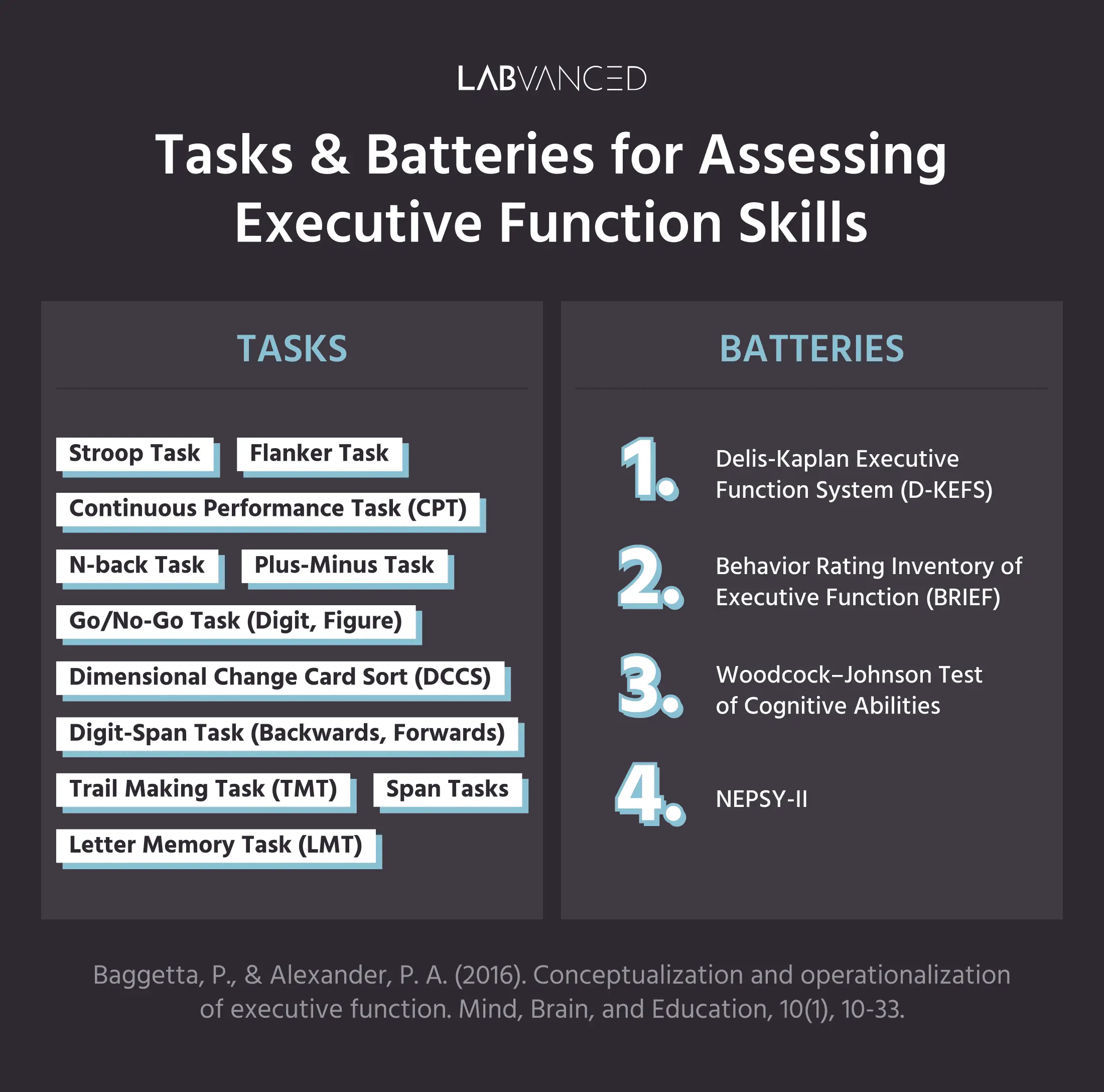

A systematic review of 106 empirical studies conducted in 2016 sought out to understand how executive functioning skills are conceptualized and operationalized in empirical research. The authors identified 109 different tasks across the literature that have been used to measure executive functioning skills. Of these 109 tasks, the authors noted that 56 were only used once - which suggests that researchers developed their own tasks to be used in the context of their specific study. The remaining 53 tasks were used multiple times (Baggetta, P., & Alexander, P. A., 2016). We selected the most commonly used executive function tasks from that list (see Table S5- Supplementary Information) and have presented them below in the order of popularity:

- Stroop Task

- Digit-Span Task (Backwards, Forwards)

- Go/No-Go Task (Digit, Figure)

- Trail Making Task (TMT)

- N-back Task

- Span Tasks

- Continuous Performance Task (CPT)

- Plus-Minus Task

- Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS)

- Flanker Task

- Letter Memory Task (LMT)

Stroop Task

- Task Description: The Stroop Task is a classic cognitive task in which participants are instructed to name the color of a word, requiring them to control their focus on the word’s color as opposed to reading it. Trials often involve presenting with the name of a color but having it written in a conflicting color. For example, the participants see the written stimuli “BLUE” but is presented with a red font color and the participants are expected to name the color of the word (ie, red).

- Executive functions and the Stroop Task: The Stroop task is an excellent measure of selective attention, cognitive flexibility and cognitive inhibition skill of a participant, as they must focus on identifying its color rather than their automatic response of reading the word. Reaction time (RT) is a common measure in Stroop tasks. (Bjekić, 2017; Timmeren, 2018).

Digit-Span task (Backwards, Forwards)

- Task Description: The Digit-Span Task involves recalling a sequence of numbers presented in a particular order. In the Digit Span Forward, participants are expected to repeat the numbers in the same order as presented, and Digit Span Backward requires the participant to repeat the sequence in reverse order (Wahlstrom, 2016).

- Executive Functions and the Digit-Span Task: The Digit span task mainly measures working memory, attention, cognitive flexibility and strong short-term memory retention (Watanabe, 2023; Weiss, 2016).

Go/No-Go Task (Digit, Figure)

- Task Description: The Go/No-Go Task requires participants to respond to a specific stimulus (mostly a "go" sign) and not respond to other stimuli (a "no-go" signal). The participants usually respond by pressing a button for “go” stimuli and by withholding their response for "no-go" stimuli. The task can be customized to use stimuli in the form of digits or figures.

- Executive Functions and the Go/No-Go Task: This task assesses skills such as response inhibition and impulse control which requires the participants to suppress and control their automatic responses. Attention regulation is another EF skill exhibited during the task (Weidacker, 2017; Bezdjian, 2009).

Trail Making Task (TMT)

- Task Description: The Trail Making Task is a well known measure of EF. It involves two parts: connecting numbers in ascending order (Part A) and connecting numbers and alphabets alternatively in ascending order (Part B). The numbers and alphabets are written inside circles and the participants are expected to connect the circles by drawing lines.

- Executive Functions and the Trail Making Task: The TMT measures EF such as the psychomotor speed, focussed attention, visuospatial search, target-directed motor tracking and updating of respondents. Part B additionally measures inhibition control and set-switching skills (Lähde, 2024; Gajewski, 2018).

N-back Task

- Task Description: The N-back Task involves the presentation of a sequence of stimuli wherein the participants have to decide whether the current stimuli is the same as “N” trials ago. The “N” could be 1, 2, etc.

- Executive Functions and the N-back Task: In this task the participants are expected to continuously adjust their recall, giving insights on EF skills such as working memory capacity, updating, sustained attention and cognitive flexibility. attention, updating, and executive functions (Gajewski, 2018).

Span Tasks

- Task Description: Memory Span tasks involve the presentation of different stimuli (verbal, arithmetic, operational or visuospatial) in a specific order and the respondents are expected to remember and recall these stimuli in the same order in which it was presented.

- Executive Functions and Span Tasks: These tasks majorly measure working memory and attentional capacity in specific domains. Updating abilities are also found to be an important EF skill in span tasks, especially in verbal and visuo-spatial working memory span tasks (McCabe, 2010; St Clair-Thompson, 2006).

Continuous Performance Task (CPT)

- Task Description: In the Continuous Performance Task (CPT), participants are required to react correctly to specific stimuli. For example, participants are expected to press on space for all letters except for ‘A’ or when they see or hear a specific word or image.

- Executive Functions and the CPT: The CPT majorly assesses sustained attention and response inhibition as it requires the participants to focus on a continuous stream of stimuli and control/inhibit their impulsivity to react to irrelevant stimuli. (Clark, 2023).

Plus-Minus Task

- Task Description: The Plus-Minus Task involves 3 conditions: Block 1 requires the participant to carry out an arithmetic operation of addition, and block 2 provides a condition of subtraction. Block 3, however, requires the participants to alternate between addition and subtraction.

- Executive Functions and the Plus-Minus Task: This task is a common measure of the executive function of cognitive flexibility and shifting (Chainay, 2021).

Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS)

- Task Description: The Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS) is a widely used standard measure of executive functions. It involves sorting cards or pictures in a particular way (eg. shape) and then switching to a different way of sorting (eg. color). The DCCS is a simplified version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

- Executive Functions and the DCCS: The DCCS is a measure of task switching and cognitive flexibility, as the participants are required to adapt to new rules spontaneously (Beaucage, 2020).

Flanker Task

- Task Description: In the Flanker Task, participants are presented with a central target stimulus (like arrow or letter) which is surrounded by flankers (congruent or incongruent stimuli). The participants are expected to respond only to the central target's specific characteristic (an arrow pointing to the left) while ignoring the flankers (arrows pointing at different directions).

- Executive Functions and the Flanker Task: This task primarily tests selective attention and response inhibition, as the participants try to focus on the target by filtering out irrelevant stimuli. Other executive functions the task activates include working memory, time perception, initiation, and motor control (Rusnáková, 2011).

Letter Memory Task (LMT)

- Task Description: The Letter Memory Task uses consonant letters as stimuli with each trial consisting of a series of five, seven or nine consonants, presented one letter at a time. The participants are required to constantly recall the last three letters after a delay (Golsteijn, 2021).

- Executive Functions and the Letter Memory Task: The LMT measures working memory, especially updating and monitoring of working memory representations (Mielicki, 2018; Miyake, 2000).

Batteries for Asessing Executive Function

Executive Functioning Batteries offer a comprehensive approach to assessing executive functions. They include multiple tasks and scales that provide a broader view of a participant’s executive function profile. These ‘official’ batteries are often protected by copyright and typically require permission to use, especially for research or clinical purposes. Because of these restrictions, many researchers prefer to use and combine the experimental tasks described above or create their own.

All the scales and tasks that are included in these batteries can be classified into performance-based tasks and behavioral ratings (by others or self-reports). The systematic review by Baggetta & Alexander in 2016 identified a few common batteries that measure executive functions. Here are a few:

- Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS)

- Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF)

- Woodcock–Johnson Test of Cognitive Abilities

- NEPSY-II

Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS)

The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) is the first nationally standardized test set to assess higher level cognitive functions in both adults and children (age 8 - 89).

- Subtests: The D-KEF includes nine subtests: Trail Making Test, Verbal Fluency Test, Design Fluency Test, Color-Word Interference Test, Sorting Test, Twenty Questions Test, Word Context Test, Tower Test and Proverb Test. It is available in two formats: The Standard Record Forms that include all nine tests and the Alternate Record Forms that include alternate versions of the sorting test, verbal fluency test, and the twenty questions tests.

- Executive Functions Assessed: There are nine components of executive functioning assessed by the D-KEF, namely, cognitive flexibility, design fluency, verbal fluency, inhibition, categorical processing, problem solving, deductive reasoning, spatial planning, and verbal abstraction.

- Applications: The D-KEF is widely used in settings such as clinical populations to assess neuropsychological conditions, including those with ADHD, autism, and dyslexia. It has also been used to study cognitive performances and executive functioning in both children and adults (Cahill, 2019; MacDonald, 2024; Ehtesabi, 2022).

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF)

The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) is a battery that provides assessment of executive functions and has several versions of it for different populations and age groups. The measure is done by informant reports and behavioral ratings by teachers and parents (Mcauley et al, 2010).

- Subtests: The BRIEF includes three indices, with a total of eight scales: Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI): Assesses Inhibition, Shifting, and Emotional Control. Metacognition Index (MI): Assesses Initiation, Working Memory, Planning/Organizing, Organization of Materials, and Monitoring. Global Executive Composite: Computed by the combination of BRI & MI (Wolrich, 2008).

- Executive Functions Assessed: The executive functioning skills assed are controlling impulses, modifying behavior, cognitive flexibility, transitioning, emotional modulation, beginning a task/activity, in-dependently generating ideas, holding information in mind, persistence, anticipating future events, setting goals, workspace, play areas, orderliness, work checking and keeping track of how behaviors affect others (Wolrich, 2008).

- Variations: The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) has several versions tailored for different age groups and specific assessment needs.

- BRIEF2: Children aged 5 to 18 (parent, teacher, and self-report forms with revised norms).

- BRIEF-P: Preschool version for younger children aged 2 to 5.

- BRIEF-SR: Self-Report version for older children and adolescents aged 11 to 18.

- BRIEF2 ADHD Form: For identifying ADHD symptoms in children.

- BRIEF-A: Adult version for individuals aged 18 to 90 (ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.-b).

Woodcock–Johnson Test of Cognitive Abilities

The Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities is a set of standardized assessments designed to evaluate a wide range of cognitive abilities and intellectual capabilities. It is in its latest 4th edition – The Woodcock-Johnson IV Tests of Cognitive (WJ-IV COG). It could be administered on children and adults (aged 2-90 years).

- Subtests: The WJ-IV COG is composed of 10 standard battery and 8 extended battery tests, namely, Oral Vocabulary, Number Series, Verbal Attention, Letter-Pattern Matching, Phonological Processing, Story Recall, Visualization, General Information, Concept Formation, Numbers Reversed, Number-Pattern Matching, Nonword Repetition, Visual-Auditory Learning, Picture Recognition, Analysis-Synthesis, Object-Number Sequencing, Pair Cancellation and Memory for Words (Dumont, 2016).

- Executive Functions Assessed: The WJ-IV COG assesses a range of executive functioning skills, including comprehension-knowledge, fluid reasoning, short-term memory, processing speed, auditory processing, visual-spatial ability, and long-term storage and retrieval (Bulut, 2021).

- Applications: The WJ-IV COG is widely used in multiple settings such as education, clinical and research domains. It has been found to help professionals in diagnosing intellectual disabilities and cognitive strengths and weaknesses of children. It has also been used to determine the eligibility for special education services. The WJ-IV COG contributes to research on cognitive abilities and is used to improve assessment practices (Floyd, 2016).

NEPSY-II

The NEPSY-II is a neuropsychological battery for preschoolers, children, and adolescents (aged 3-12) (Hooper, S.R. (2013). The subtests of the battery enables its users to administer it in combinations according to the need of the child or the assessment requirement.

- Subtests: The NEPSY-II includes 32 subtests and 4 delayed tasks and these are further categorized into six content domains: Attention and Executive Functioning, Language, Social Perception, Memory and Learning, Sensorimotor, and Visuospatial Processing (Davis, 2010).

- Executive Functions Assessed: The executive functions assessed by NEPSY-II include Inhibition, Monitoring, Self-Regulation, Vigilance, Selective and Sustained Attention Processes, Capacity to Create, Preserve, and Adapt a Response Set, Nonverbal Problem Solving, Preparing and Managing a Multifaceted Response and Figural Fluency (Davis, 2010).

- Applications: The NEPSY-II is used widely for the diagnosis of various clinical conditions as well as in school based interventions. It provides insights into cognitive, academic, social, and behavioral issues of children (Davis, 2010).

Assessing Executive Function Skills Online

With the advancement in technology and research, the administration of assessments on participants remotely has been adopted by educational institutes, research facilities and clinical settings all around the world. Despite its wide usage, assessing executive functions online can still come with its set of challenges. However, with the appropriate measures and safeguards in place, these can be accounted for and controlled in a remote setting: Here are a few common challenges that need to be kept in mind during the experimental design stage and set up when implementing executive function tasks online:

- Technical Barriers: Technical barriers such as unreliable and slow internet connectivity is an important challenge to consider. A slow connection can cause a delay in presenting different stimuli and recording reaction time data which ultimately diminishes the accuracy of the results. s A slower internet connection could be more prevalent for individuals coming from low socioeconomic (SES) backgrounds, but still in higher SES brackets, an unexpected internet disconnection can still occur. (Ahmed, 2022; Biagianti, 2019; Ernst, 2024; Segura, 2021).

- Equipment Accessibility: Studies have shown that participants can face limitations with regards to the accessibility of certain equipment, such as movable or document cameras (Ahmed, 2022; Segura, 2021). This is particularly relevant if executive function batteries that are administered are not in a computerized form and the participant is expected to fill out tests by hand.

- Devices and Technological Expertise: Research has shown that observable variations in cognitive functioning scores can be found based on the type of device that the participant used to perform the test, as well as the computer proficiency of the participants (Liu, 2022). Participants with low technological expertise also require more time for completing the tasks (Ernst, 2024).

- Environmental Distractions and Participant Engagement: Remote assessments are significantly affected by environmental distractions such as noise, pets and the presence of other factors in the surroundings. This could disrupt the attention and engagement of participants and further cause biases in task outcomes (Ahmed, 2022; Liu, 2022; Ernst, 2024; Segura, 2021). There are also instances where lack of supervision has impacted participant engagement (Biagianti, 2019).

Even though there are multiple challenges found in the administration of executive functioning tasks or batteries, research has suggested different ways to enhance its effectiveness. These include using reliable internet connectivity for both the examiner (in the case they are present) and examinee, encouraging the participants to minimize distractions in surroundings and implementing a requirement for the participants to confirm that they are mentally prepared for the assessment and free from any distractions (Ahmed, 2022; Liu, 2022). Undertaking the assessments from a familiar setting, like from home, has been proven to reduce anxiety during the assessments (Segura, 2021).

When it comes to designing remote assessments few strategies are found to help in enhancing its effectiveness. Here are a few:

- User-friendly platforms: Making use of user friendly platforms that are easy to navigate (Ahmed, 2022).

- **Clear and Simple Task Design: Choosing tasks that are validated with simple presentation and clear stimuli with instructions (Ahmed, 2022).

- Controlled Task Progression: Ensuring that the examiner has control over how the task progresses (eg, keyboard inputs) and in the case where the examiner is not present, ensuring that the experiment loads and progresses properly before it is published (Ahmed, 2022).

- Relevant Material Adaptation: Presenting tasks in formats that are easy to handle in remote settings (eg, using powerpoint presentations as opposed to PDFs, if necessary) or making sure that the computerized tasks are representative of the original pen-and-paper task (Ahmed, 2022).

- Chunking of Information: Presenting information in smaller manageable chunks to maintain attention, especially in children (Ahmed, 2022). For example, if you have long task instructions, maybe break it down into two steps instead of having it all on a single view.

- Short Duration: Designing tasks that are short in duration to enhance engagement of participants (Biagianti, 2019).

- **Inclusion of Varied Tasks: Incorporating a variety of tasks that are different from each other to maintain interest of participants (Biagianti, 2019).

- Compatibility with Multiple Devices: Ensuring that the designed web-based tasks are compatible across multiple devices for standardized administration (Liu, 2022).

- Adaptability of Tests: Usage of test batteries that are adaptable for different socioeconomic and cultural groups and contexts (Segura, 2021).

- Incorporation of Breaks: Incorporating breaks throughout the assessment (Ernst, 2024).

In addition to all the above strategies, it is important to maintain clear communication throughout the assessments. Building rapport, communicating expectations prior to the assessment, and providing comprehensive instructions are crucial for remote assessments (Ahmed, 2022; Liu, 2022; Segura, 2021; Ernst, 2024).

The majority of the strategies, such as controlling for device compatibility and environmental settings, are addressed by Labvanced via how it handles experimental control.

Conclusion

Executive functions are crucial for the advancement of cognitive development and goal-oriented behavior. The specific tasks and comprehensive batteries designed to assess executive functioning help us understand how individuals interact with their environment to achieve goals. With advancements in technology, these assessments can now be effectively administered remotely across diverse populations and age groups, offering new opportunities for both research and clinical applications!

References

- Ahmed, S. F., Skibbe, L. E., McRoy, K., Tatar, B. H., & Scharphorn, L. (2022). Strategies, recommendations, and validation of remote executive function tasks for use with young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z2cu3

- Baggetta, P., & Alexander, P. A. (2016). Conceptualization and operationalization of executive function. Mind, Brain, and Education, 10(1), 10–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12100

- Beaucage, N., Skolney, J., Hewes, J., & Vongpaisal, T. (2020). Multisensory stimuli enhance 3-year-old children’s executive function: A three-dimensional object version of the Standard Dimensional Change Card Sort. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 189, 104694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2019.104694

- Behavior rating inventory of executive function. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.-a). https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/behavior-rating-inventory-of-executive-function

- Behavior rating inventory of executive function. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. (n.d.-b). https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/behavior-rating-inventory-of-executive-function

- Bezdjian, S., Baker, L. A., Lozano, D. I., & Raine, A. (2009). Assessing inattention and impulsivity in children during the Go/Nogo Task. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27(2), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151008x314919

- Biagianti, B., Fisher, M., Brandrett, B., Schlosser, D., Loewy, R., Nahum, M., & Vinogradov, S. (2019). Development and testing of a web-based battery to remotely assess cognitive health in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 208, 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.01.047

- Bjekić, J., Živanović, M., Purić, D., Oosterman, J. M., & Filipović, S. R. (2017). Pain and executive functions: A unique relationship between Stroop task and experimentally induced pain. Psychological Research, 82(3), 580–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-016-0838-2

- Bulut, O., Cormier, D. C., Aquilina, A. M., & Bulut, H. C. (2021). Age and sex invariance of the Woodcock-Johnson IV tests of cognitive abilities: Evidence from Psychometric Network modeling. Journal of Intelligence, 9(3), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence9030035

- Cahill, M. N., Dodzik, P., Pyykkonen, B. A., & Flanagan, K. S. (2019). Using the delis–kaplan executive function system tower test to examine ADHD sensitivity in children: Expanding analysis beyond the summary score. Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology, 5(3), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-019-00068-0

- Chainay, H., Joubert, C., & Massol, S. (2021). Behavioural and ERP effects of cognitive and combined cognitive and physical training on working memory and executive function in healthy older adults. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 17(1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.5709/acp-0317-y

- Clark, C. A., Cook, K., Wang, R., Rueschman, M., Radcliffe, J., Redline, S., & Taylor, H. G. (2023). Psychometric Properties of a combined go/no-go and continuous performance task across childhood. Psychological Assessment, 35(4), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001202

- Cragg, L., & Gilmore, C. (2014). Skills Underlying Mathematics: The role of executive function in the development of mathematics proficiency. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 3(2), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2013.12.001

- Davis, J. L., & Matthews, R. N. (2010). NEPSY-II Review. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 28(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282909346716

- Dumont, R., Willis, J. O., & Walrath, R. (2016). Clinical interpretation of the woodcock–johnson IV tests of cognitive abilities, academic achievement, and Oral Language. WJ IV Clinical Use and Interpretation, 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-802076-0.00002-5

- Ehtesabi, A., Faramarzi, S., Ehteshamzadeh, P., Bakhtiarpour, S., & Ghamarani, A. (2022). The effectiveness of training package based on executive functions of delis-kaplan on reading skill of dyslexic students. Journal of Adolescent and Youth Psychological Studies, 3(2), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.61838/kman.jayps.3.2.12

- Ernst, J. R., Pan, S. E., & Carlson, S. M. (2024). Remote assessment of the association between Early Executive Function and mathematics skills. Infant and Child Development, 33(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2534

- Floyd, R. G., Woods, I. L., Singh, L. J., & Hawkins, H. K. (2016). Use of the woodcock–johnson IV tests of cognitive abilities in the diagnosis of intellectual disability. WJ IV Clinical Use and Interpretation, 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-802076-0.00010-4

- Gajewski, P. D., Hanisch, E., Falkenstein, M., Thönes, S., & Wascher, E. (2018). What does the N-back task measure as we get older? relations between working-memory measures and other cognitive functions across the lifespan. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02208

- Golsteijn, R. H., Gijselaers, H. J., Savelberg, H. H., Singh, A. S., & de Groot, R. H. (2021). Differences in habitual physical activity behavior between students from different vocational education tracks and the association with Cognitive Performance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063031

- Hooper, S.R. (2013). NEPSY-II. In: Volkmar, F.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3_353

- Liu, Y., Schneider, S., Orriens, B., Meijer, E., Darling, J. E., Gutsche, T., & Gatz, M. (2022). Self-administered web-based tests of executive functioning and Perceptual Speed: Measurement Development Study with a large probability-based survey panel. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(5). https://doi.org/10.2196/34347

- Lähde, N., Basnyat, P., Raitanen, J., Kämppi, L., Lehtimäki, K., Rosti-Otajärvi, E., & Peltola, J. (2024). Complex executive functions assessed by the trail making test (TMT) part B improve more than those assessed by the TMT part A or digit span backward task during vagus nerve stimulation in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1349201

- MacDonald, R., Baker‐Ericzén, M., Roesch, S., Yeh, M., Dickson, K. S., & Smith, J. (2024). The latent structure of the delis–kaplan system for autism. Autism Research, 17(4), 728–738. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.3122

- MCAULEY, T., CHEN, S., GOOS, L., SCHACHAR, R., & CROSBIE, J. (2010). Is the behavior rating inventory of executive function more strongly associated with measures of impairment or executive function? Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 16(3), 495–505. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355617710000093

- McCabe, D. P., Roediger, H. L., McDaniel, M. A., Balota, D. A., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2010). The relationship between working memory capacity and executive functioning: Evidence for a common executive attention construct. Neuropsychology, 24(2), 222–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017619

- Mielicki, M. K., Koppel, R. H., Valencia, G., & Wiley, J. (2018). Measuring working memory capacity with the letter–number sequencing task: Advantages of visual administration. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 32(6), 805–814. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3468

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1999.0734

- Reimers, K. (2019). Evaluation of cognitive impairment. The Clinician’s Guide to Geriatric Forensic Evaluations, 65–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-815034-4.00003-9

- Rusnáková, Š., Daniel, P., Chládek, J., Jurák, P., & Rektor, I. (2011). The executive functions in frontal and temporal lobes: A flanker task intracerebral recording study. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 28(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/wnp.0b013e31820512d4

- Segura, I. A., & Pompéia, S. (2021). Feasibility of remote performance assessment using the Free Research Executive Evaluation Test Battery in adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.723063

- St Clair-Thompson, H. L., & Gathercole, S. E. (2006). Executive functions and achievements in school: Shifting, updating, inhibition, and working memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59(4), 745–759. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470210500162854

- Timmeren, T. V., Daams, J. G., van Holst, R. J., & Goudriaan, A. E. (2018). Compulsivity-related neurocognitive performance deficits in gambling disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 84, 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.11.022

- Wahlstrom, D., Weiss, L. G., & Saklofske, D. H. (2016). Practical issues in WISC-V administration and scoring. WISC-V Assessment and Interpretation, 25–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-404697-9.00002-9

- Watanabe, N. (2023). An empirical study of supporting executive function in Family Education with mental abacus. Frontiers in Education, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.851093

- Weidacker, K., Whiteford, S., Boy, F., & Johnston, S. J. (2017). Response inhibition in the parametric go/no-go task and its relation to impulsivity and subclinical psychopathy. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(3), 473–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2015.1135350

- Weiss, L. G., Saklofske, D. H., Holdnack, J. A., & Prifitera, A. (2016). WISC-V. WISC-V Assessment and Interpretation, 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-404697-9.00001-7

- WOLRAICH, M. L., PERRIN, E. C., DWORKIN, P. H., & DROTAR, D. D. (2008). CHAPTER 7 - Screening and assessment tools. Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics, 123–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-04025-9.50010-6