Attention tasks are used by researchers to understand and quantify attention, a seemingly simple cognitive process that is actually very difficult to truly understand. Attention tasks can be conceptualized to measure different facets of attention, such as selective attention or sustained attention. But, due to the intricate nature of attention, there actually may be some overlap between these tasks.

Key Sections:

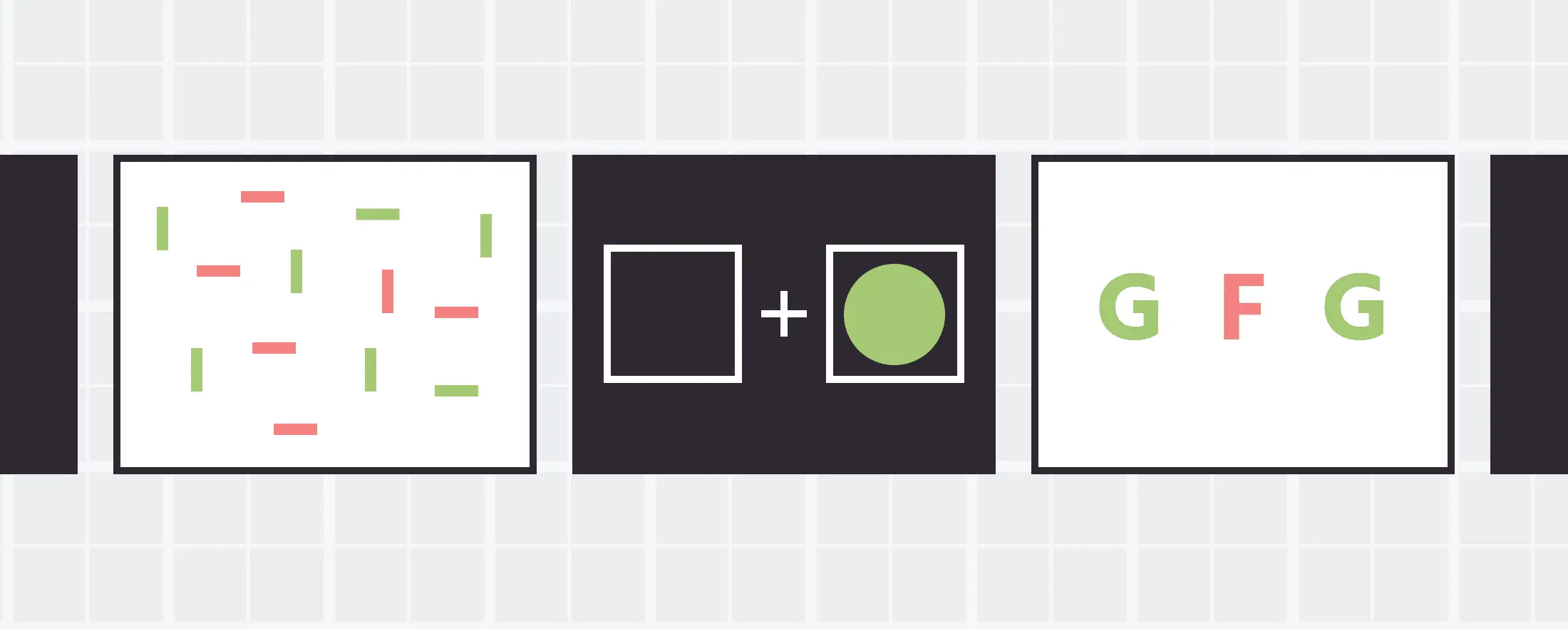

Attention tasks can be organized into four categories, reflecting different attentional processes mainly categorized into four types:

- Selective Attention Tasks: Such tasks aim to understand selective attention, the ability to prioritize and focus on selected relevant stimuli while ignoring irrelevant stimuli (DeGangi, 2017). For example, identifying a specific letter on a screen filled with distractor letters.

- Divided Attention Tasks: These tasks assess the ability to process and focus on more than one piece of information or stimulus at a time (Cristofori & Levin, 2015). For example, reading something while listening to music.

- Sustained Attention Tasks: Sustained attention tasks assess the ability to maintain focus on a particular information or stimulus over extended periods of time (Ko et al., 2017). For example, continuously tracking a moving object on a screen without losing focus.

- Shifting Attention Tasks: These tasks aim to understand attention shifts, the ability to efficiently redirect focus from a stimulus or one perceptual feature of a stimulus to another (Von Suchodoletz et al., 2017). For example, sorting cards by color, then switching to sorting them by shape.

While these various tasks have been developed by researchers to study specific aspects of attention, it’s important to note that there may be instances where overlapping attentional processes occur– such as selective attention being supported by shifting or even sustained attention! Thus, keep that in mind when conducting your research.

While these various tasks have been developed by researchers to study specific aspects of attention, it’s important to note that there may be instances where overlapping attentional processes occur– such as selective attention being supported by shifting or even sustained attention! Thus, keep that in mind when conducting your research.

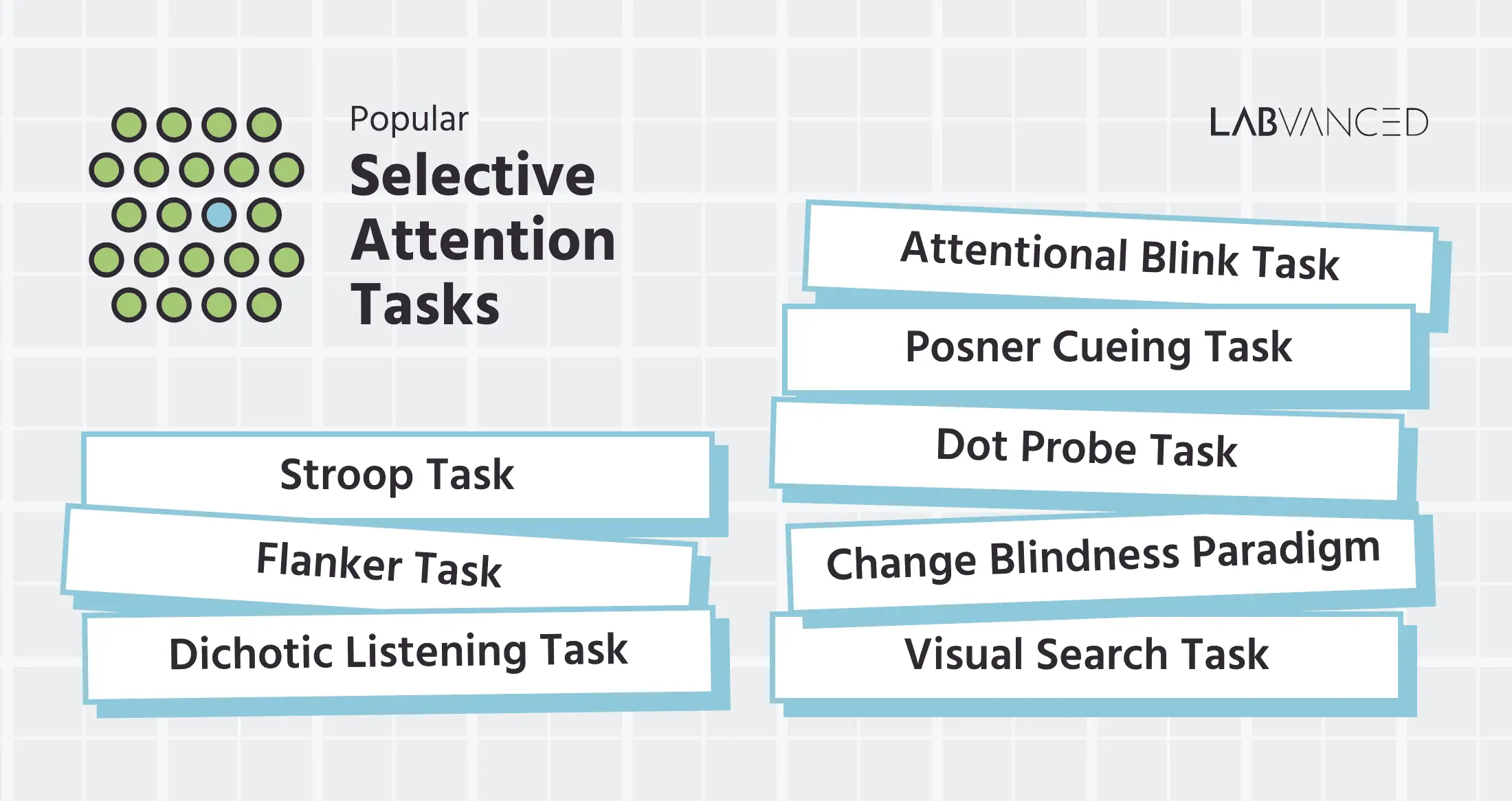

Selective Attention Tasks

Selective attention tasks are designed to measure the ability of individuals to focus on selected stimuli and ignore others. These tasks help us in understanding how individuals navigate complex environments, prioritize information, and maintain goal-directed behavior.

Key tasks that assess selective attention include the following:

Stroop Task

The Stroop task is a common measure of selective attention. The participants are presented with a colour word written in a different colour (eg., the word RED written in green colour). The participants are expected to name the colour in which the word is written (green) and not the word (RED) (Migliaccio et al., 2020). Stroop tasks are also used as a measure of other attentional processes such as sustained attention (Huang et al., 2023).

- Letter Stroop Task: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/2866

- Multimodal Stroop Task: https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/27056

Flanker Task

In the Flanker task, participants would be presented with a central target stimulus which is surrounded by irrelevant non- target stimuli. The participants are required to focus only on the direction given by the target stimulus (eg., a letter or an arrow) and ignore the irrelevant stimuli flanking on either side (Baghdadi et al., 2021).

- Flanker Arrows Task: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/27061

Dichotic Listening Task

In this task, the participants would hear two different words (or sentences) simultaneously in both, left and right ears. Based on the task specification, the participant would be required to repeat the words heard by both ears or to ignore the words heard by one ear and repeat what was heard by the other ear (Moncrieff et al., 2013).

Attentional Blink Task

Attentional blink (AB) is a phenomenon that highlights the limitations of our visual attention over time. In this task, participants view a rapid stream of letters and are asked to identify specific targets within that stream. The Attentional Blink task specifically measures how quickly we can process visual information in a sequence. The second stimulus when closely presented with the first often causes the participants to not detect the second one (Zivony & Lamy, 2021).

- Attentional Blink: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/2867

Posner Cueing Task

The Posner Cueing Task, or Posner paradigm, is a psychological test designed to assess attention and attention deficits. In this task, participants start by looking at a fixation point, followed by a cue (valid or invalid) that directs their attention to one side of the screen. After a short delay, a target appears, and participants must respond to it. It is also a common measure of reaction time (Machner et al., 2018).

- Posner Cueing Task: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/37918

Dot Probe Task

The dot probe task examines how quickly attention shifts between different stimuli. In a version of the task, two stimuli are presented in different locations on the screen. One stimulus has an emotional value attached to it (eg., an angry face) and another with a neutral value (neutral face). A probe then appears (a dot) in either of the locations of the stimuli and the participants are required to identify the dot's position. The reaction time taken to locate the dots reveals any biases in attention toward certain emotions (van et al., 2017).

- Simon Dot Study: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/27054

- Dot Probe: https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/34738

Change Blindness Paradigm

Change blindness highlights how significant changes in visual stimuli go unnoticed due to the lack of attention. In a version of the task, participants are presented with image pairs and are asked to find changes within the images (Andermane et al., 2019).

- Change Blindness Flicker Paradigm: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/31898

Visual Search Task

The Visual Search Task measures the ability to scan a visual scene to identify specific information or objects. In a simple version of it, participants are required to locate a target item from a visual scene and ignore the distractor items. Visual search tasks can be divided into continuous search tasks (multiple targets and distractors) and single-frame search tasks (decide if the target is present or not) (Hokken et al., 2022).

- Visual Search Task: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/27150

- Multi-user: Animal Word Search Game: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/62483

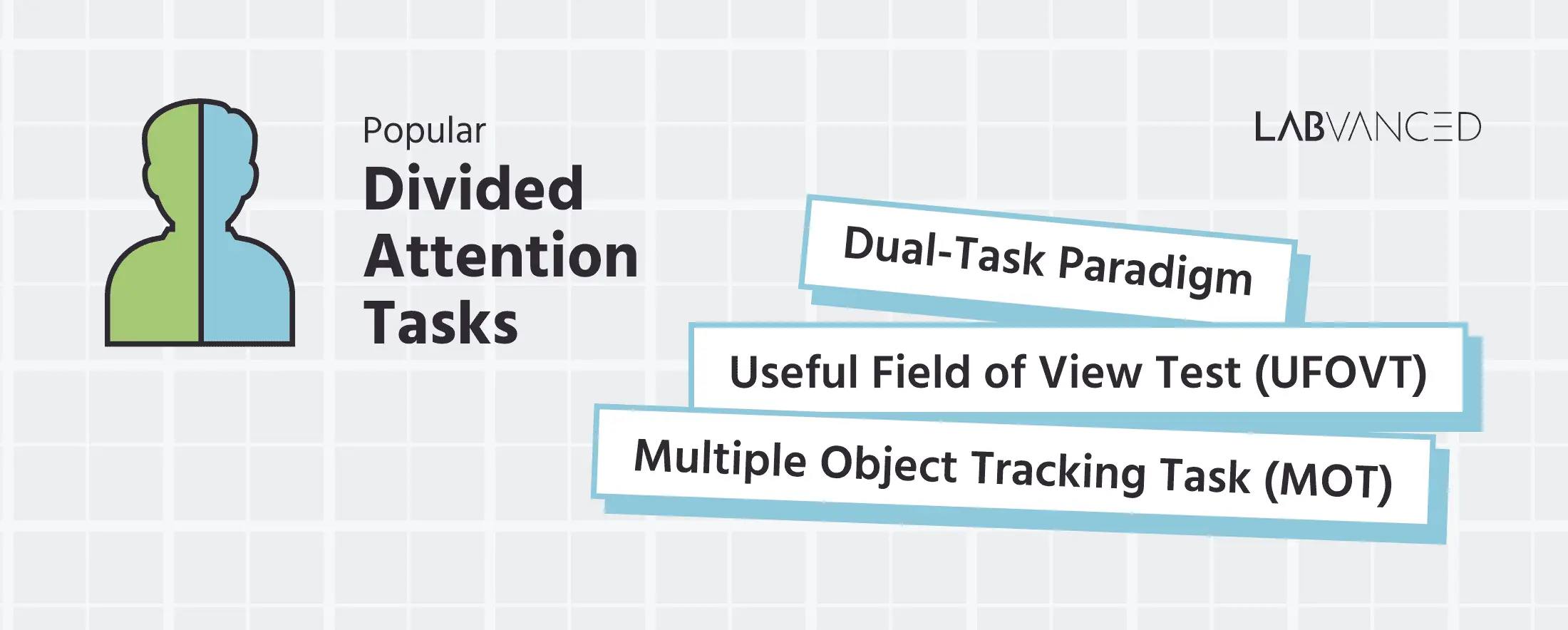

Divided Attention Tasks

Divided attention tasks assess the ability to multitask or process multiple streams of information simultaneously. These tasks help in understanding how attention influences motor abilities and cortical responses, help in identifying conditions like dementia, and provide insights into other cognitive processes (Angekumbura et al., 2022).

Key tasks that assess divided attention include the following:

Dual-Task Paradigm

The Dual-Task Paradigm assesses divided attention by requiring participants to perform two tasks at once. The primary task typically involves the use of motor and cognitive skills, while the secondary task is unrelated to the primary task and is included to create competition and evaluate resource sharing (Esmaeili, 2021; Angekumbura et al., 2022). For instance, saying if a tone is high, medium, or low in pitch (auditory-vocal task) and pressing a button for specific numbers (visual-manual task) (Courage et al., 2015).

Useful Field of View Test (UFOVT)

The Useful Field of View Test (UFOVT) is a measure of how well we can process information in peripheral vision (outside the direct line of sight). This is a widely used task to predict crash risk in drivers. In a computerised version of the task, participants are presented with an image (eg., truck or car) in a central location and peripheral objects in different locations on the screen. They are expected to recall the image presented in the central location and identify the locations of the peripheral objects (Cardoso et al., 2018).

Multiple Object Tracking Task (MOT)

In the Multiple Object Tracking Task, a sequence of moving objects is presented on screen. The participants are required to monitor and track a certain number of target objects simultaneously from a larger set of objects. The MOT provides a valid measure of individual differences in visual attention (Meyerhoff & Papenmeier, 2020).

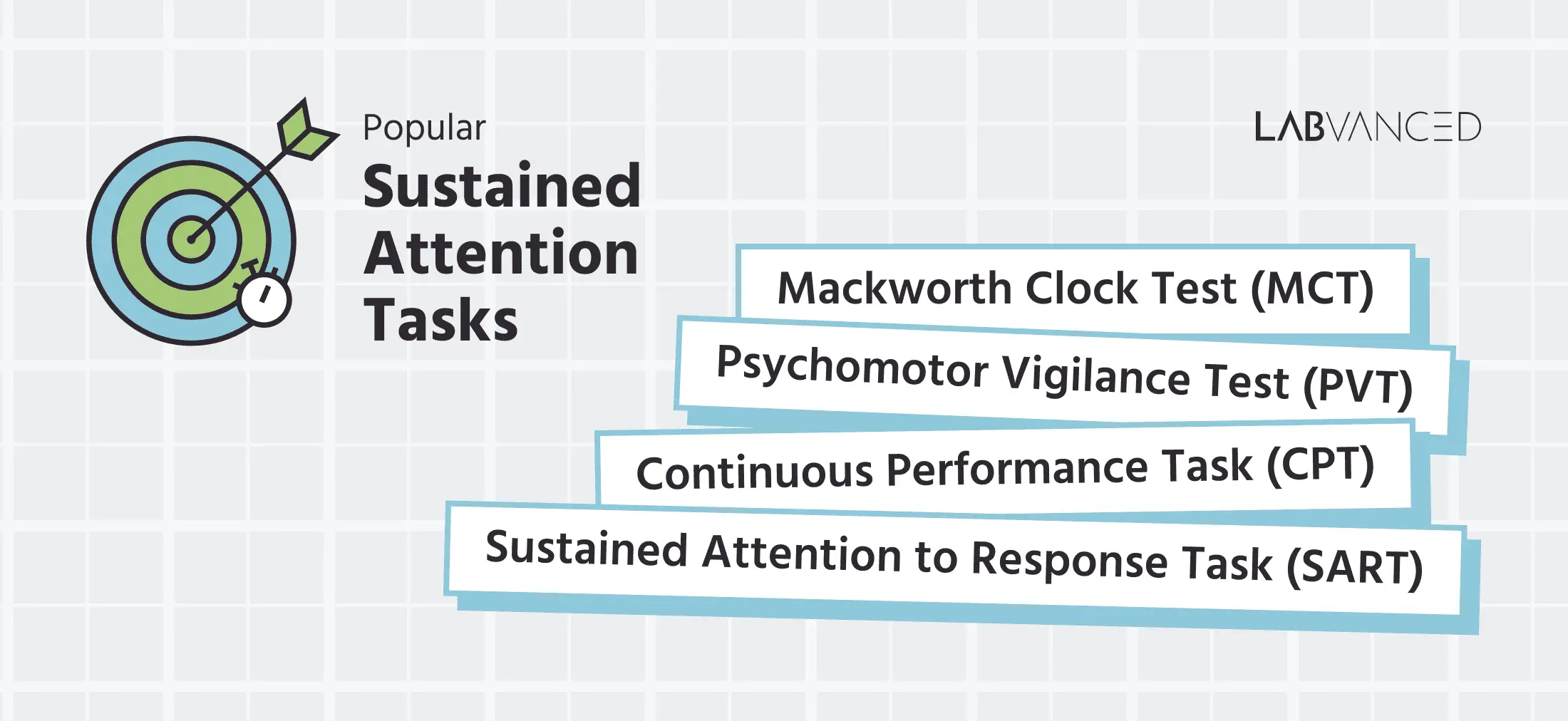

Sustained Attention Tasks

Sustained attention tasks or vigilance tasks assess the ability of an individual to maintain focus over a long period. These tasks often include the continuous presentation of target and non-target stimuli to which the participants must respond to or refrain from responding.

Key tasks that assess sustained attention include the following:

Continuous Performance Task (CPT)

The Continuous Performance Task (CPT) is a widely used measure of sustained attention. In this task, participants are presented with various stimuli and are required to respond only to a specific stimuli and withhold from responding to others, or respond to all stimuli except for one particular target stimuli. For instance, press on the spacebar when the alphabet ‘Q’ appears and not for any other alphabets displayed (Loh et al., 2022; Song & Rosenberg, 2021). CPT is sometimes referred to as the 'vigilance task’.

Sustained Attention to Response Task (SART)

The Sustained Attention to Response Task (SART) is another commonly used measure of sustained attention with an emphasis on response inhibition. In a version of this task, participants are presented with various stimuli and are expected to respond to non-target stimuli (eg., names of animals) and restrain from responding to target stimuli (eg., names of food) (Vallesi et al., 2021).

- Sustained Attention Task (SART): Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/36592

Mackworth Clock Test (MCT)

The Mackworth Clock Test (MCT) is a test developed to assess sustained attention to simple stimuli. Subsequently, different versions of the test have been developed and used with various samples. In one version of the task, participants are presented with a clock featuring 60 points, each in a circular shape, displayed on a screen. One of the points contains a white dot that jumps to the next point every 1.5 seconds. At random intervals, the dot skips one point and jumps to the next, taking 3 seconds instead of 1.5 seconds. Participants are required to react to these double-jumps by pressing the spacebar (Gacek et al., 2024).

Psychomotor Vigilance Test (PVT)

The Psychomotor Vigilance Test is a sustained attention task used to assess the ability of an individual to be alert and respond to visual stimuli presented. The standard form of the test lasts for 10 mins, but there are other versions developed with varying duration such as PVT-3 (3 mins). In this task, a visual stimulus (a box) is presented on the screen and the participants are required to press the spacebar every time a millisecond counter appears in the box (Huang et al., 2023).

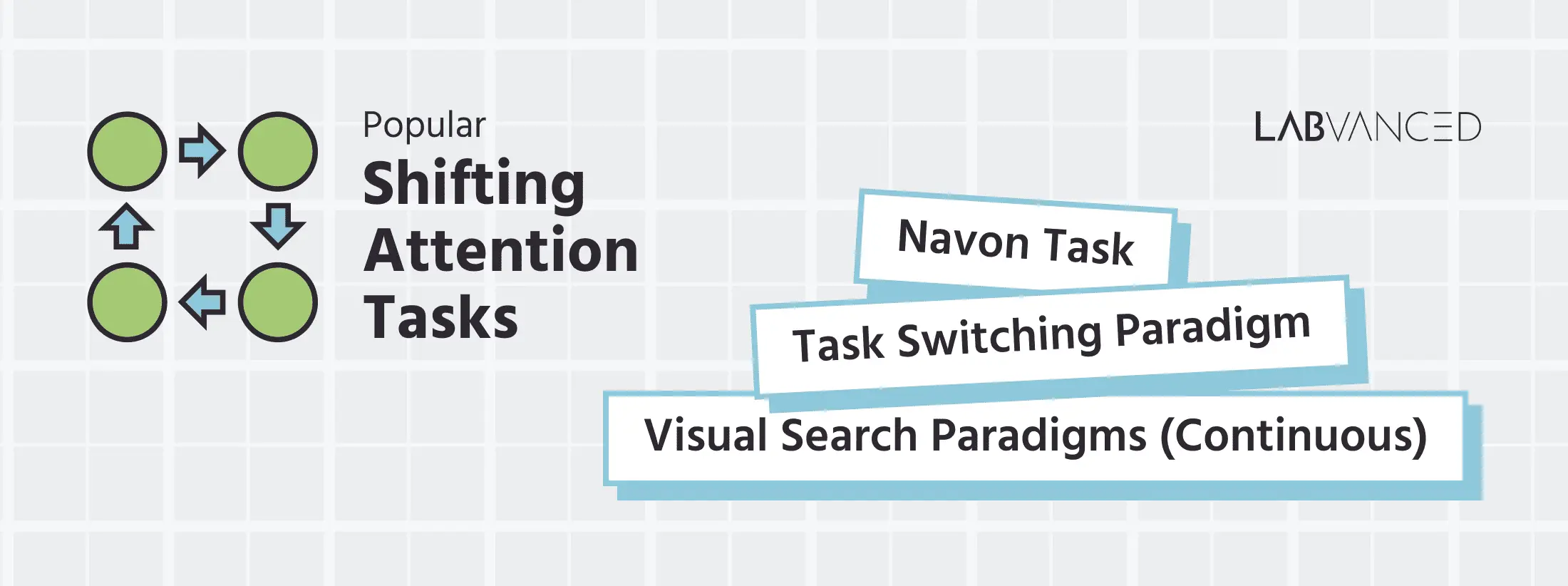

Shifting Attention Tasks

Shifting attention tasks, also known as attention shift tasks, assess our ability to switch focus between different tasks or different elements within the same task. Shifting tasks can cover a broad range of attention-shifts, requiring the participant to shift between locations, objects, object attributes, stimulus-response rules, and tasks (Wager, T. D., Jonides, J., & Reading, S., 2004). Ultimately, shifting tasks provide insights into cognitive flexibility and adaptability in various environments.

Key tasks that assess shifting attention include the following:

Task Switching Paradigm

Task Shifting Paradigms are designed to assess how an individual could maintain their attention on one particular task and also effectively shift the attention to a different task when required. In this task, participants are provided with two tasks and a rule/cue on when to shift between the tasks (Hughes et al., 2013).

- Cued Task Switching: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/39449

Visual Search Paradigms (Continuous)

Depending on how you look at it, visual search tasks, especially its more complex variations, are considered not just as a measure of selective attention but also shifting attention. In an example of such a task, participants can be presented with a continuous stream of words (RSVP format) and are required to identify the words based on a predefined category (eg., synonyms of “small”). When a cue is given to change the category (eg., to synonyms of “big”), the participants are required to shift their attention from the previous category to a new category of words. Visual search tasks such as spatial configuration searches require serial shifting of attention and the demand for attentional resources often increases with the number of search items (Lee & Han, 2020).

- Visual Search Task: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/27150

- Multi-user: Animal Word Search Game: https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/62483

Navon Task

The Navon Task is a simple test to measure how attention shift occurs between global and local elements of a figure. In this task, participants are provided with global letters (large letters) made of local letters (small letters). For eg., a letter “H” composed of small “X”s. The global letters and local letters were always different and the participants were required to press on a yellow sticker key when either the global or local letters were “X” and on a red sticker key when neither the global nor the local letters were “X” (Richard & Lajiness-O’Neill, 2015).

- Navon Task: Try it out or import it to your account https://www.labvanced.com/page/library/36082

Conclusion

Understanding attention is crucial for comprehending the cognitive functions of individuals. Different attention tasks have been developed as a gateway to explore the various forms of attention and their underlying processes. With the wide variety of attention tasks available, researchers can effectively investigate individual differences, cognitive mechanisms, and the interplay of attention across diverse environments and populations!

References

Andermane, N., Bosten, J. M., Seth, A. K., & Ward, J. (2019). Individual differences in change blindness are predicted by the strength and stability of visual representations. Neuroscience of Consciousness, 2019(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/nc/niy010

Angekumbura, C. D., Dilshani, T. H. T., Perera, K. T. D., Jayarathna, S. N., Kahandawarachchi, K. A. D. C. P., & Udara, S. W. I. (2022). A review of methods to detect divided attention impairments in alzheimer’s disease. Procedia Computer Science, 198, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.12.228

Baghdadi, G., Towhidkhah, F., & Rajabi, M. (2021). Assessment methods. Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Attention, 203–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-90935-8.00005-6

Cardoso, M., Fulton, F., Callaghan, J. P., Johnson, M., & Albert, W. J. (2018). A pre/post evaluation of fatigue, stress and vigilance amongst commercially licensed truck drivers performing a prolonged driving task. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 25(3), 344–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803548.2018.1491666

Courage, M. L., Bakhtiar, A., Fitzpatrick, C., Kenny, S., & Brandeau, K. (2015). Growing up multitasking: The costs and benefits for cognitive development. Developmental Review, 35, 5–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2014.12.002

Cristofori, I., & Levin, H. S. (2015). Traumatic brain injury and cognition. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 579–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-63521-1.00037-6

DeGangi, G. A. (2017). Treatment of attentional problems. Pediatric Disorders of Regulation in Affect and Behavior, 309–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-810423-1.00008-8

Esmaeili Bijarsari, S. (2021). A current view on dual-task paradigms and their limitations to capture cognitive load. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648586

Gacek, M., Smoleń, T., Krzywoszański, Ł., Bartecka-Śmietana, A., Kulasek-Filip, B., Piotrowska, M., Sepielak, D., & Supernak, K. (2024). Effects of school-based neurofeedback training on attention in students with autism and intellectual disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-024-06400-8

Hokken, M. J., Krabbendam, E., van der Zee, Y. J., & Kooiker, M. J. (2022). Visual selective attention and visual search performance in children with CVI, ADHD, and dyslexia: A scoping review. Child Neuropsychology, 29(3), 357–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2022.2057940

Hsieh, S., & Allport, A. (1994). Shifting attention in a rapid visual search paradigm. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 79(1), 315–335. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1994.79.1.315

Huang, H., Li, R., & Zhang, J. (2023). A review of visual sustained attention: Neural mechanisms and computational models. PeerJ, 11. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15351

Hughes, M. M., Linck, J. A., Bowles, A. R., Koeth, J. T., & Bunting, M. F. (2013). Alternatives to switch-cost scoring in the task-switching paradigm: Their reliability and increased validity. Behavior Research Methods, 46(3), 702–721. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0411-5

Ko, L.-W., Komarov, O., Hairston, W. D., Jung, T.-P., & Lin, C.-T. (2017). Sustained attention in real classroom settings: An EEG study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00388

Lee, J., & Han, S. W. (2020). Visual search proceeds concurrently during the attentional blink and response selection bottleneck. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 82(6), 2893–2908. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-020-02047-6

Loh, H. W., Ooi, C. P., Barua, P. D., Palmer, E. E., Molinari, F., & Acharya, U. R. (2022). Automated detection of ADHD: Current trends and future perspective. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 146, 105525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105525

Machner, B., Könemund, I., von der Gablentz, J., Bays, P. M., & Sprenger, A. (2018). The ipsilesional attention bias in right-hemisphere stroke patients as revealed by a realistic visual search task: Neuroanatomical correlates and functional relevance. Neuropsychology, 32(7), 850–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000493

Meyerhoff, H. S., & Papenmeier, F. (2020). Individual differences in visual attention: A short, reliable, open-source, and multilingual test of multiple object tracking in Psychopy. Behavior Research Methods, 52(6), 2556–2566. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01413-4

Migliaccio, R., Tanguy, D., Bouzigues, A., Sezer, I., Dubois, B., Le Ber, I., Batrancourt, B., Godefroy, V., & Levy, R. (2020). Cognitive and behavioural inhibition deficits in neurodegenerative dementias. Cortex, 131, 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2020.08.001

Moncrieff, D., Jorgensen, L., & Ortmann, A. (2013). Psychophysical auditory tests. Handbook of Clinical Neurophysiology, 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7020-5310-8.00011-9

Richard, A. E., & Lajiness-O’Neill, R. (2015). Visual attention shifting in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 37(7), 671–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2015.1042838

Song, H., & Rosenberg, M. D. (2021). Predicting attention across time and contexts with functional brain connectivity. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 40, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.12.007

Vallesi, A., Tronelli, V., Lomi, F., & Pezzetta, R. (2021). Age differences in sustained attention tasks: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28(6), 1755–1775. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-01908-x

van Rooijen, R., Ploeger, A., & Kret, M. E. (2017). The dot-probe task to measure emotional attention: A suitable measure in comparative studies? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24(6), 1686–1717. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-016-1224-1

von Suchodoletz, A., Fäsche, A., & Skuballa, I. T. (2017). The role of attention shifting in orthographic competencies: Cross-sectional findings from 1st, 3rd, and 8th grade students. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01665

Zivony, A., & Lamy, D. (2021). What processes are disrupted during the attentional blink? an integrative review of event-related potential research. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 29(2), 394–414. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-01973-2