The Psychology of the Ebbinghaus Illusion

The Ebbinghaus Illusion, although it has been studied for more than a 100 years, is still relevant in today’s research world, being applied even to online experiments, as psychologists and neuroscientists try to understand the inner workings behind this illusion.

What is the Ebbinghaus Illusion?

Named after the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850-1909), the Ebbinghaus Illusion (sometimes also referred to as Titchener Circles) is an optical illusion that shows how size perception can be manipulated by the surrounding shapes.

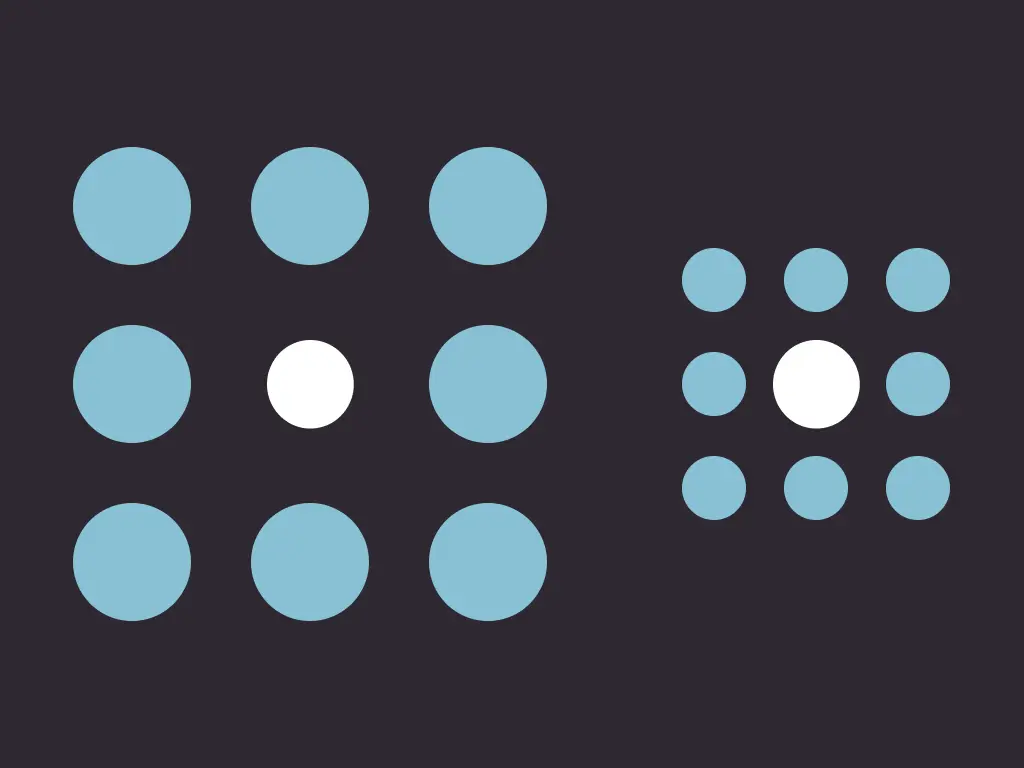

In the Ebbinghaus illusion, a stimulus that is surrounded by larger shapes will appear smaller than when it is surrounded by smaller shapes. See Fig.1 below. Most people would eagerly agree that the red circle (the test disk) on the left is smaller than the one on the right.

Fig 1: Demonstration of the Ebbinghaus Illusion

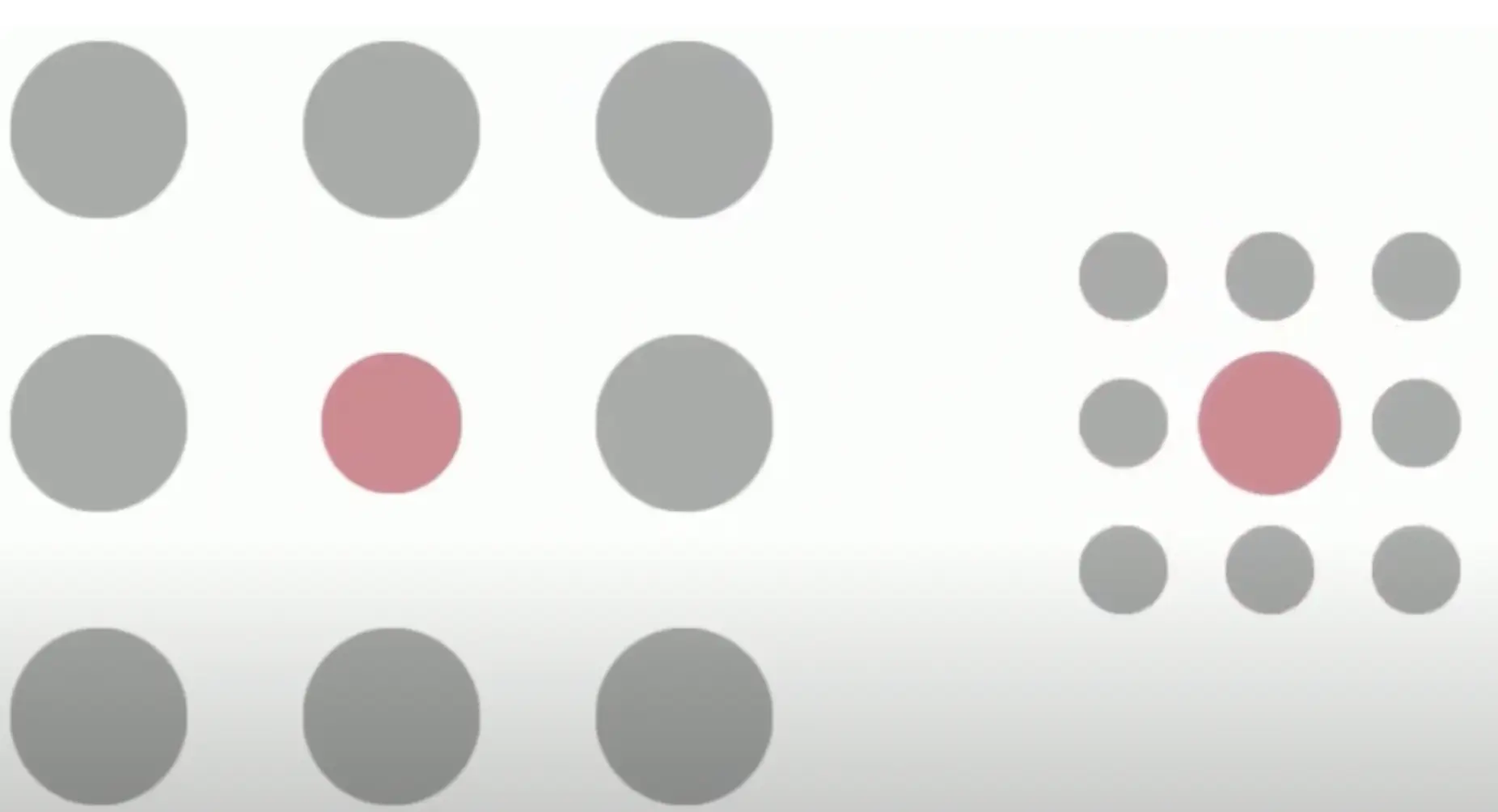

In reality, they are the same size, see Fig 2 below. The red shapes are, in fact, the same size and the shapes that surround them (inducers) are heavily related to this perceptual phenomenon.

Fig 2: The centered shapes are the same size even though perception suggests otherwise.

This perceptual phenomenon makes it challenging for participants to match the red circles with each other.

Online Experiments with the Ebbinghaus Illusion

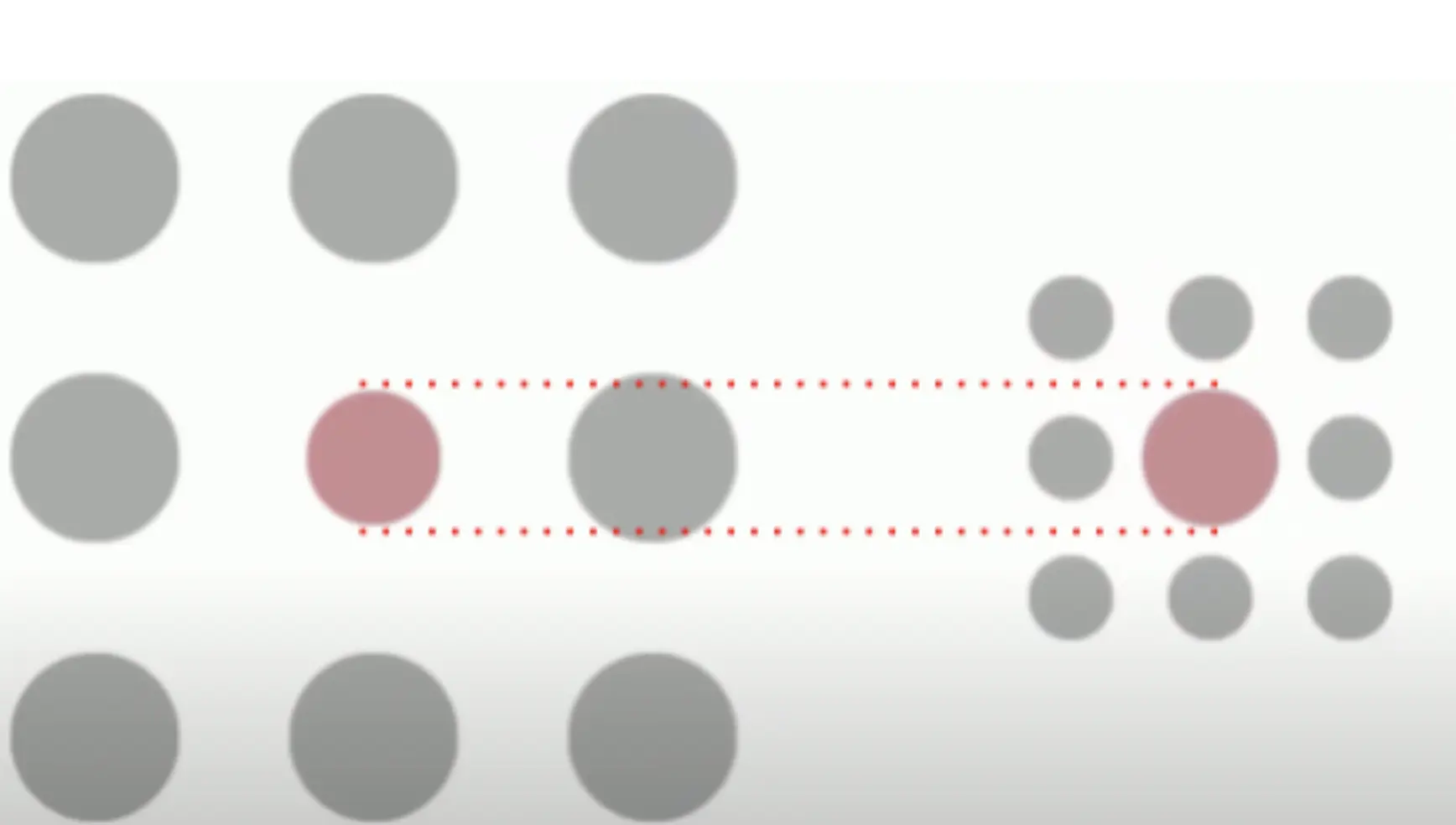

As experiments shift to online platforms, traditionally static illusions like the Ebbinghaus Illusion have followed suit. Now, through the Labvanced platform, Fig 3., users from all over the world can participate in an Ebbinghaus Illusion study easily while university and post-doc students can use the pre-built programming features as a template for their own experiment with just a few simple clicks.

Fig 3: A participant trying to match the two red circles (test disks) of the Ebbinghaus Illusion as accurately as possible without being influenced by the surrounding circles (inducers) while on the Labvaced platform.

Psychology Studies Using the Ebbinghaus Illusion

As more is discovered about the brain, and theories continue to develop, new areas and research questions about the Ebbinghaus Illusion (i.e. Titchener Circles) arise. Below, we take a look at a few studies that have the Ebbinghaus Illusion at their core.

Cognitive Processes

Using the Ebbinghaus Illusion as the heart of the experiment, researchers have tested cognitive processes, trying to explain the mechanisms that give rise to this illusion or at least influence participant performance.

Memory: Rey and colleagues showed that memory bias has an influence on how participants perceive the illusion. Using two different groups, the researchers showed that when participants had a learning phase, then their performance. The learning phase indicated that memory was playing a role in the performance as the two groups had different results when trying to match the test disks in size. The researchers hypothesized that the role of memory on perception for this task performance has to do with the theory that perception and memory share common resources and rely on the same motor-sensory systems in the brain (Rey et al., 2015).

Working memory load: Another study considered how working memory can impact results of the Ebbinghaus Illusion. When participants were given a high working memory load, they are more likely to be distracted by the size of the surrounding disks/inducers and face more illusion perceptually. This suggests that available cognitive control is key to performing well in this task (de Fockert & Wu, 2009).

Developmental Psychology

Another study demonstrated that age plays a role in how the illusion is perceived. Doherty and colleagues used the Ebbinghaus Illusion and cued young (primary school children) or older participants (university students) to choose which test disk is larger (i.e. the two-alternative forced-choice paradigm). The test disks were always different in size and the participants had to indicate which of the two looked bigger.

The results were surprising when the researchers found that primary school children had a higher discrimination accuracy percent than university students. The researchers concluded that children are able to discriminate with more accuracy than adults in misleading contexts (Doherty et al., 2010).

Abnormal Psychology

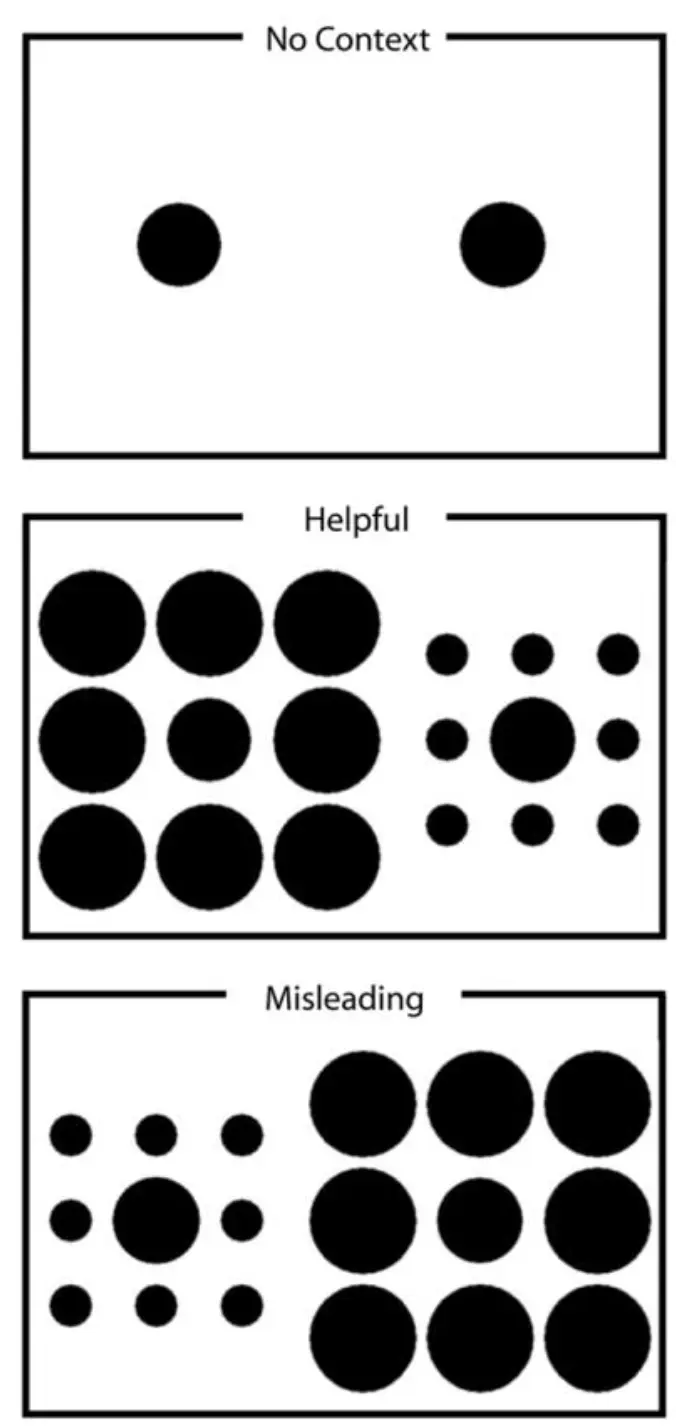

The illusion has even been applied in the field of abnormal and clinical psychology. One study assessed participants that were at ultra high-risk for a psychotic episode and compared their performance to healthy controls. The participants were asked to distinguish between the size of two target circles that varied across conditions. The ‘helpful condition’ made judgement easier while the ‘misleading condition’ was more difficult (stimuli illustrated in the image on the left). By contrast, there was the ‘no-context condition’ where targets appeared without any reference.

The illusion has even been applied in the field of abnormal and clinical psychology. One study assessed participants that were at ultra high-risk for a psychotic episode and compared their performance to healthy controls. The participants were asked to distinguish between the size of two target circles that varied across conditions. The ‘helpful condition’ made judgement easier while the ‘misleading condition’ was more difficult (stimuli illustrated in the image on the left). By contrast, there was the ‘no-context condition’ where targets appeared without any reference.

The researchers found that the at-risk for psychosis group was less affected by the ‘misleading condition,’ performing better than controls. This was, in turn, associated with greater negative symptoms and also role functioning (Mittal et al., 2015).

Biology

A genome-wide association study by Zhu et al. even found substantial evidence for a genetic basis explaining the Ebbinghaus Illusion! In this large study with over 2800 participants, the researchers took both biological and psychosocial samples. Both single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and genes were analyzed, 55 SNPs and 7 genes were associated with overestimation. The researchers concluded that overestimation in the Ebbinghaus Illusion can be partially explained through heritability with their models estimating that genes have a 34.3% effect on performance outcome (Zhu et al., 2021).

Closing Remarks

While the Ebbinghaus Illusion has been around for a long time, it is still relevant in today’s research world as students and labs use online experiments and learn more about what gives rise to the perceptual phenomenon. From a closer look at cognitive processes to studies that bring biology to the table, new insights are still shedding light on the Ebbinghaus Illusion making it as interesting and intriguing as ever.

References

de Fockert, J. W., & Wu, S. (2009). High working memory load leads to more Ebbinghaus illusion. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 21(7), 961-970.

Doherty, M. J., Campbell, N. M., Tsuji, H., & Phillips, W. A. (2010). The Ebbinghaus illusion deceives adults but not young children. Developmental science, 13(5), 714-721.

Mittal, V. A., Gupta, T., Keane, B. P., & Silverstein, S. M. (2015). Visual context processing dysfunctions in youth at high risk for psychosis: Resistance to the Ebbinghaus illusion and its symptom and social and role functioning correlates. Journal of abnormal psychology, 124(4), 953.

Rey, A. E., Vallet, G. T., Riou, B., Lesourd, M., & Versace, R. (2015). Memory plays tricks on me: Perceptual bias induced by memory reactivated size in Ebbinghaus illusion. Acta psychologica, 161, 104-109.

Zhu, Z., Chen, B., Na, R., Fang, W., Zhang, W., Zhou, Q., ... & Fang, F. (2021). A genome-wide association study reveals a substantial genetic basis underlying the Ebbinghaus illusion. Journal of Human Genetics, 66(3), 261-271.