The Placebo Effect

What is the Placebo Effect?

Have you ever felt the effects of something, only to find that you did not actually receive the true object or experience? This is the Placebo Effect: the sensation of benefiting from a treatment without actually receiving it. The effect comes from our beliefs and expectations- essentially, we can convince ourselves that something worked for us and that we feel better (Harvard Health, 2021).

Placebos, or fake treatments, have been used in many areas of psychology. They can be as simple as placing a large bandage on a child’s imaginary cut or as complex as fake opioids and analgesic medications. Researchers in Health Psychology use placebos to assess the effectiveness of a drug or treatment as compared to not receiving any treatment. Rather than simply not treating a control group, administering a placebo allows the researchers to examine psychological effects of the drug. When participants think they are receiving a drug, but are actually taking a fake version, the only effect on their body is psychological. This isolated event capitalizes on our ability to convince ourselves that we are experiencing a treatment.

The Placebo Effect also employs some elements of Behavioral Psychology in the form of classical conditioning. The extent to which placebos rely on conditioning versus pure expectation has been debated, but Stewart-Williams and Podd, 2004 concluded that both play a role. In humans, it has been observed that the placebo effect can occur either by conditioning a response, creating a sense of expectation, or both at once.

Even when participants know they are receiving a placebo treatment, some statistically significant changes have been noted between pre- and post-treatment health. While the participants in a study by Park et al. in 1965 displayed confounding variables such as desire for treatment and the knowledge that the placebo trial would only last a week, this shows that in some instances we can convince ourselves that a treatment is working even when we know it is fake. The participants had entered a clinic seeking care for psychological problems, underwent an evaluation, then left the clinic with sugar pills that they knew contained no medicine. After one week of the sugar pills, 93% of the participants showed some kind of improvement in their psychological condition. The use of sugar pills is what comes to mind for most people when they hear the word "placebo," but placebos can come in other forms as well.

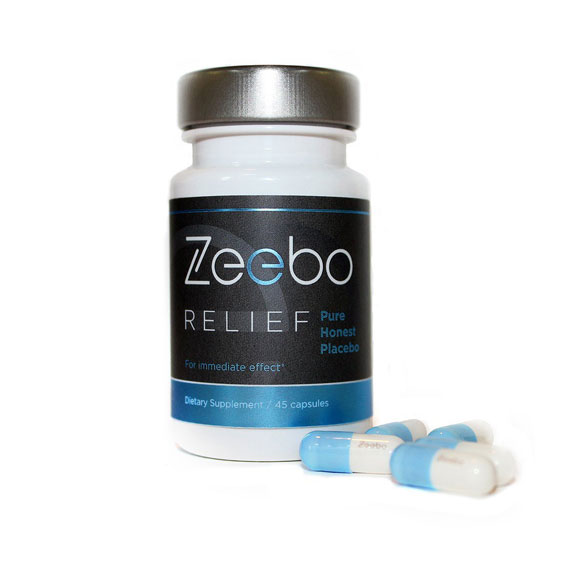

Fig. 1: Zeebo pills, marketed as self-administered placebos

Online Experiments with the Placebo Effect

The placebo effect can be seen even in remote studies, as discussed later in the Research section of this blog. While some studies rely on the in-person, laboratory experience to fuel the expectations of the placebo treatment, online researchers can use their anonymity to shape participants’ perception of the experience.

Labvanced offers several features that can be used to study the placebo effect online in a simple, in-browser format:

- Multi-User Studies: Build a task for participants to work together, for example, before and after receiving a real or placebo educational module about cooperation.

- Longitudinal Studies: Track participants across time with tasks and/or surveys related to the treatment they have been receiving.

- Groups and Sessions: Set up your Groups within the Study Design tab to include participants who match specific demographic qualities. Keep Groups separate by assigning unique Sessions to each one, ensuring each participant sees the course of the study that matches their treatment type.

- Learn more about Study Design here

These key features of Labvanced can be used in a variety of studies to enhance experimental designs and answer current questions about the placebo effect.

Current Research Using the Placebo Effect

Although the Placebo Effect was first named in the 1700’s and has probably been observed much earlier than that, researchers are still discovering new aspects of this phenomenon today. Many different fields of psychology have connected this effect to related works, and in some cases, have even observed this effect remotely.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

In a 2012 study of therapy for chronic insomnia, Dr. Colin Espie and colleagues observed the placebo effect via an online application. The study involved participants undergoing behavioral therapy in 3 different conditions: the treatment being tested, a placebo treatment that was specifically designed to seem as credible as possible, and the participants’ individual treatment as normal. The experimental and placebo conditions were housed on the website Sleepio, which studies and aims to treat sleep disorders. While the researchers found the best benefit from the true experimental treatment, “it should be noted that [the placebo treatment] relative to [treatment as normal] did show some positive effects… to confirm that there was a placebo effect for at least a proportion of participants” (Espie et al. 2021). Therefore, a small but noteworthy finding of this study was that the placebo effect can be seen in online fabricated therapy modules, where no physical drug was administered and no physical researcher was ever seen.

Do Participants Understand the Meaning of Placebos?

While we have already discussed that some instances exist of the placebo treatment being effective even when participants know it is inert, some researchers question if participants even understand the meaning of the word “placebo.” If the participants do not understand the significance (or lack thereof) of a placebo treatment, then can we be certain whether a true placebo effect is occurring?

Through a Qualtrics survey, Dr. Rosanne Smits and colleagues conducted an online study of participants’ knowledge of the term “placebo,” when placebos should be used, and how people would like the treatment to be explained to them if they were offered a placebo of some kind. The study found that on average, participants scored about 80% correct on a test of their knowledge about placebos, but only 20% of participants knew that deception is not required to administer a placebo treatment. The researchers also found that participants would be more willing to try a placebo treatment for a psychological issue versus a physical, bodily issue. The researchers concluded that people in general likely prefer to not be deceived; they would rather be informed of the fake nature of a treatment rather than experience the placebo effect unknowingly (Smits et al. 2021). This is something to consider if your research involves placebos or if you plan to use them in the future.

Closing Remarks

Numerous studies have measured the placebo effect with and without deception. In both cases, it has been noted that there is an interaction between conditioning and expectations. The size of the effect may be large or small, but it is agreed that the human brain can convince itself of almost anything!

Placebos can be used both in-person and online. While some settings rely on the sensations invoked by people in white coats and physical pills, placebos can also be treatments such as online training modules or simple thought exercises.

What will you test using the placebo effect?

References

Espie, C. A., Kyle, S. D., Williams, C., Ong, J. C., Douglas, N. J., Hames, P., & Brown, J. S. (2012). A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep, 35(6), 769-781.

Harvard Health (2021, December 13). The power of the placebo effect. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mental-health/the-power-of-the-placebo-effect

Kirsch, I. (2004). Conditioning, expectancy, and the placebo effect: comment on Stewart-Williams and Podd (2004).

Park, L. C., & Covi, L. (1965). Nonblind placebo trial: an exploration of neurotic patients' responses to placebo when its inert content is disclosed. Archives of general psychiatry, 12(4), 336-345.

Placebo pills [Electronic Image]. (2015). Zeebo. Retrieved April 14, 2022, from https://zeeboeffect.com/

Price, D. D., Finniss, D. G., & Benedetti, F. (2008). A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: recent advances and current thought. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 59, 565-590. Sleepio.com. (2020). Sleepio. Retrieved April 14, 2022, from https://www.sleepio.com/ Smits, R. M., Veldhuijzen, D. S., Olde Hartman, T., Peerdeman, K. J., Van Vliet, L. M., Van Middendorp, H., ... & Evers, A. W. (2021). Explaining placebo effects in an online survey study: Does ‘Pavlov’ ring a bell?. PloS one, 16(3), e0247103.

Stewart-Williams, S., & Podd, J. (2004). The placebo effect: dissolving the expectancy versus conditioning debate. Psychological bulletin, 130(2), 324.