Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test has a long tradition in the field of psychology and today it is even being conducted online. This task is a powerful way to measure cognitive and flexibility reasoning, still proving popular today amongst cognitive psychologists and researchers. Read on to learn more about the in’s and out’s of the Wisconsin card sorting task, its history, how it can be conducted online, and the powerful research findings that it can unveil!

History of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task

So, why does the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) have ‘Wisconsin’ in its name? It has nothing to do with the visual stimuli and everything to do with its origin story. The WCST dates back to 1948 and the University of Wisconsin. Researcher Esta Berg wrote the paper A Simple Objective Technique for Measuring Flexibility in Thinking and therein lies the beginning of the WCST. Based on experiments that were conducted at the University of Wisconsin Primate Laboratory, rhesus monkeys showed a response to positive and negative stimuli shifts where the stimulus object reward was the only clue that the problem was changed. This suggested a possible technique that could be transferred to humans for measuring abstraction and shift sets as a means of quantitatively measuring reasoning and thinking. From this, the WCST was inspired. Notably, in this paper, Berg thanked researchers David Grant and Harry Harlow (who is famous for this attachment theory).

About the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

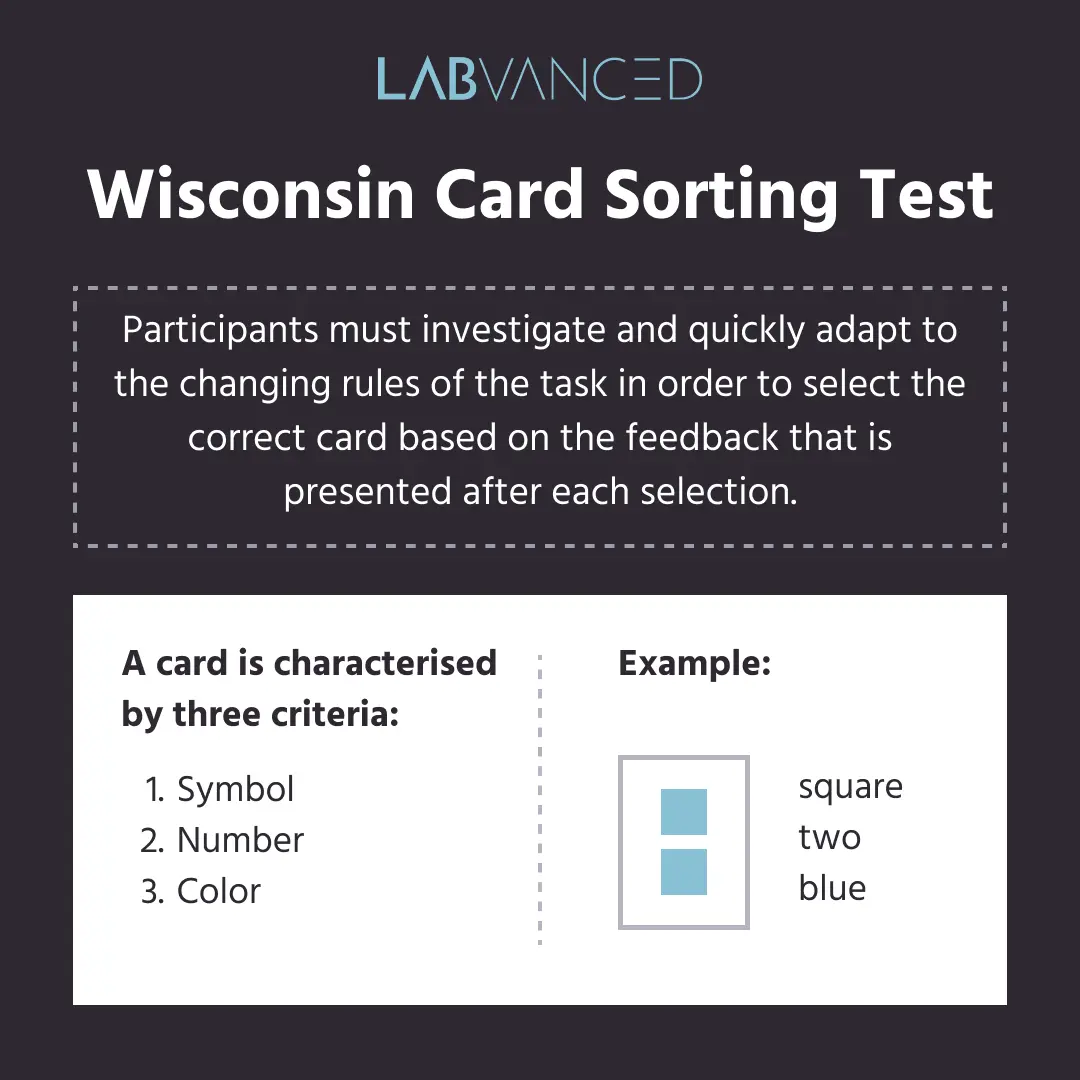

So what is the Wisconsin card sorting task all about? In the WCST, participants are presented with several cards. On the card, there are different visual stimuli determined by three criteria, the:

- symbol (ie. shape),

- number of the shapes, and

- the color.

In the image below, you can see a card that represents:

- A square

- The number 2

- The color blue

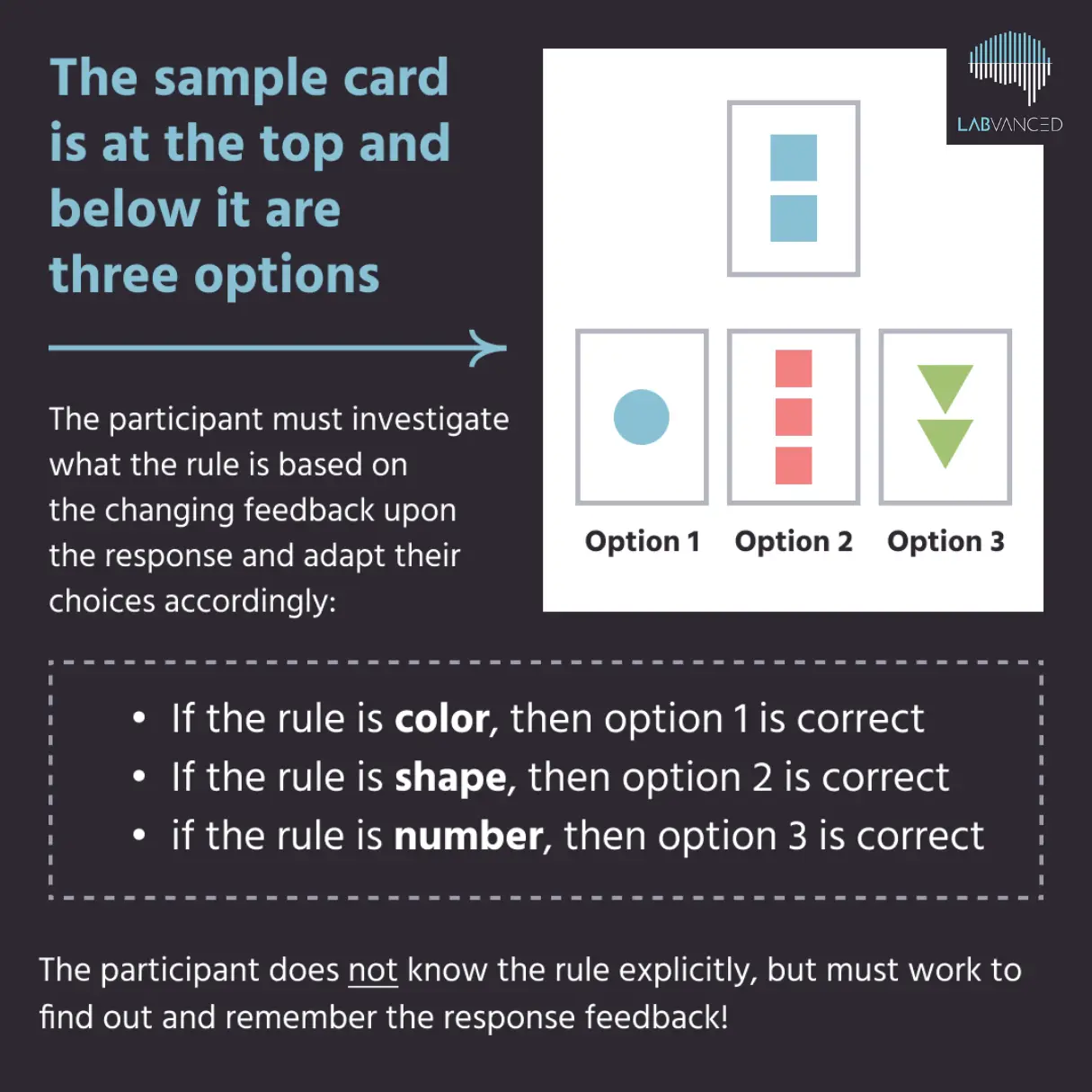

During the task, the participant has a target card that defines the ‘rule’ they are looking for. Below that card, there are three more cards with variations in the criteria (i.e. representing different possibilities in shape, number, and color). The participant has to guess what the target criteria is in order to get a ‘Correct’ feedback response. In the example below, you can see a sample trial for the Wisconsin Sorting Card Test. The participant sees the target card and has to pick from 3 options.

- If the rule is color, then option 1 is correct

- If the rule is shape, then option 2 is correct

- If the rule is number, then option 3 is correct

The only clue on what the rule is comes from the feedback that is presented upon the feedback that is presented upon choice selection.

Cognitive Functions

Research assessing cognitive functions using the WCST states its relevance for the following:

- Executive function

- Task switching

- Cognitive reasoning

- Cognitive flexibility

- Working memory

- Problem solving ability

- Response maintenance

In addition to its relevance for studying the above cognitive functions, some advantages of using the Wisconsin card sorting task include it not being language-based, thus instructions are straightforward and the level of instructions needed can be minimal (Gomez-de-Regil, 2020).

Measurement and Data from the WCST

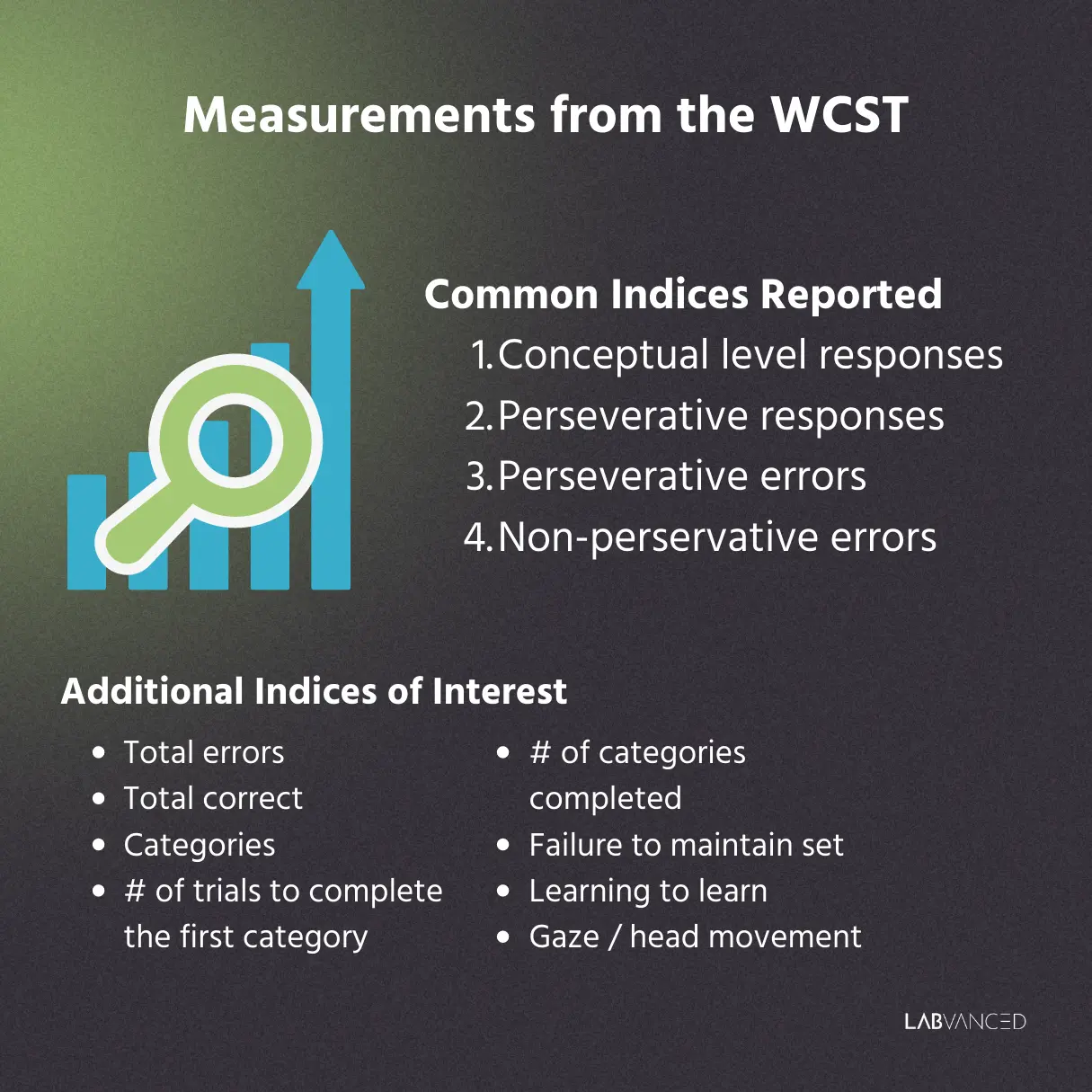

When conducting the Wisconsin card sort task, certain indices and measurements are gathered that are specific to the test. These include, but are not limited to:

- Conceptual level responses: The number of three or more correct trials which occurred consecutively.

- Perseverative responses: The number of trials which involve perseverative behavior. Perseverative response or behavior is defined as when the participant matches a card based on the same criteria used in the previous trial, regardless of the response being right or not.

- Perseverative errors: The number of wrong trials which involve perseverative behavior

- Non-perseverative errors: The number of incorrect trials which did not involve perseverative behavior

From the above, perseverative errors and responses are most commonly used to indicate cognitive flexibility. Since there is a wide body of research using the WCST, it is also possible to see the following indicators being used (Chiu & Lee, 2019):

- Total errors: The total number of trials where the answer was wrong

- Total correct: The total number of trials where the answer was correct

- Categories: The number of categories where a specific rule applies

- The number of categories completed: The total number of categories that were completed successfully; sometimes referred to as ‘categories achieved’

- Number of trials to complete the first category: The number of trials it took to complete the first category successfully

- Failure to maintain set: The number of wrong trials which occurred after five or more consecutively correct trials.

- Learning to learn: The participant’s average change in conceptual efficiency across successive categories

- Gaze and/or head movement: In the case where eye tracking and/or head tracking are included, physiological measurements on gaze and/or head position can also be gathered.

Possible Confounds to Consider

As with any measure, it is important to control for potential confounds that can influence the results of the test, including the WCST. Possible confounds to consider include age- and educational-related effects as they have been reported to affect the results with younger participants performing better (Miranda et al., 2019). With regards to age, it is relevant to note here that the WCST is one of the most commonly used paradigms for measuring executive function in children. When administering the Wisconsin card sorting test, it is used in children who are 5 years old at up. Even though, from a developmental perspective, children that are younger can switch from one rule to another. Tests for young children with fewer rules or dimensions (such as only shape and color) and one switch do exist, such as the Dimensional Change Card Sort (Czapka & Festman, 2021).

Also worth mentioning is the growing level of interest in determining as to whether the WCST is a culture-free test, meaning that culture can possibly confound results, with some researchers highlighting the importance of developing certain versions to account for this variation. Another point to consider is the method of administration, with some researchers showing that there are no differences between manual and computerized/online versions of the Wisconsin card sort task in healthy populations while other disagree and go the further step of saying there may be even greater differences when administering this paradigm to clinical populations (Aran Filippetti, Krumm, & Raimondi, 2019). Furthermore, it is also common to see researchers control for variables such as intelligence as it is an important predictor of executive functions, socioeconomic status, and lexicon size (Czapka & Festman, 2021).

WCST Scores: Uses

As study goals can vary, below are the most common uses of the scores obtained from the Wisconsin card sort task:

- Description of the participants’ clinical profile: to quantify cognitive processes of a specific clinical profile.

- Comparison of clinical profiles within groups: to quantify and compare the cognitive processes of a specific clinical profile, such as comparing between patients with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) with moderate-to-severe TBI patients.

- Treatment outcome: where the main focus is the effect of treatment and intervention and the Wisconsin sorting card test is used as a measure to quantify changes in cognitive processing.

- Inclusion criterion: by using the certain scores of the WCST, certain participants can be included or excluded in a study.

Performing the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Online

A lot of neuropsychological tests are being performed online nowadays, including the WCST.

Using the Wisconsin Card Sort online for your study comes with many advantages, including:

- Being easy to build

- Quickly shareable with participants

- Advanced data gathering, like reaction time and gaze from our webcam-based eye tracking.

- Advancing the body of research available and developing the field

Try out or import the online WCST for your next study. Below is a preview of how implementing the WCST-64 in Labvanced would look like:

Example of WCST-64 Data Recorded in Labvanced

In the image below, you can see what some of the data recorded from a Labvanced-based WCST-64 study looks like. The columns represent variable values like: the number of correct responses, the current rule, whether the rule changed, the reaction time, and characteristics of the selected card, as well the target card, such as its color, number, shape and number.

Findings and Experiments Using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task

The WCST is used in both clinical and healthy populations to assess cognitive processes. There is a large body of research that makes use of this classic experimental paradigm. Some examples of experiments and findings can be found below. Additionally to the areas discussed below, the Wisconsin card sorting test has been administered to study disorders such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), fetal alcohol syndrome, epilepsy, hydrocephalus, autism spectrum disorders, learning disorders, prefrontal damage, post traumatic stress disorder, and more.

Stroke Patients

The WCST is one of the most commonly used measures for evaluating stroke patients’ executive functions. In a study by Chiu, Wu, Hung, & Tseng, published in 2017, the validity of the Wisconsin card sort task was assessed in patients with strokes by placing a special focus on the ecological, discriminative, and convergent validities of the test while measuring daily living activities. The researchers found that even though the WCST has poor ecological validity for patients with stroke, the discriminative and convergent validities were both found to be acceptable. From the indices of the task, the authors found that the “number of completed categories” and the “total number correct” measures were the best to use when determining the stroke patients’ levels of living independently.

Substance Abuse Disorders

In 2019, Faustino, Oliveira, and Lopes investigated the diagnostic precision of the WCST as an instrument for measuring executive functioning in participants with substance abuse disorders. Specifically they looked at the specificity and sensitivity of this neuropsychological instrument when comparing the participants with substance abuse disorder to healthy controls from the general population. The sample was made up of 587 participants and the substance abuse participants consisted of three groups: opioid use disorder under treatment in a therapeutic community, opioid use disorder under treatment with harm reduction and methadone maintenance, and alcohol use disorder in a therapeutic community. The researchers found that the WCST results between groups were significantly different, demonstrating the test’s strong discriminant validity.

Schizophrenia

In schizophrenic patients, impaired executive functions are a prominent cognitive problem. An estimated 68-85% of schizophrenics have been found to have impaired executive functions. Thus, the WCST is a common measure for assessing executive functions in this clinical population. Researchers and clinicians need to conduct tests from time to time in order to track treatment progress, but also to develop effective treatment plans that can improve executive functions. Due to the need of conducting such cognitive tests multiple times, the test-retest reliability is an important discussion topic for administering the WCST in schizophrenic patients. A study by Chiu & Lee pointed out that the Wisconsin card sorting test has acceptable test-retest reliability within their sample study. They found that the three indices have excellent test-retest reliability (i.e, “Number of Categories Completed,” “Total Number Correct,” and “Conceptual Level Responses”) and that two more indices have good test-retest reliability (ie., “Perseverative Responses” and “Perseverative Errors”). While the authors addressed limitations in their study, such findings show the importance of considering test-retest reliability for repeated measures assessments like the Wisconsin card sort task.

TBI

A review has shown that the WCST is a common measure for assessing executive functions in different TBI populations. After the occurrence of the TBI, the average time for patients with the condition in case studies ranged from 4 years to 62 years while in studies with multiple participants, the average time after occurrence ranged from 6 weeks to 23.5 years. Randomized controlled trials also make use of the Wisconsin sorting card test when assessing the impact of a medical treatment. Clinical trials that assessed TBI patients using the WCST for determining intervention effectiveness focused on treatments like: sertraline, growth hormone therapy, or rehabilitation programs like neuro-feedback, CogSmart, or vocational problem-solving. Furthermore, with regards to the scores, the most common reported indices in TBI patients are: perseverative errors, categories completed, and perseverative responses. The review also includes findings comparing mean scores of WCST perseverative errors and categories in studies with TBI Patients. For example, patients with mild TBI average 22.10 perseverative errors, compared to 16.34 perseverative errors in a group of healthy controls, versus 41.7 perseverative errors in a group of mild-to-severe TBI patients (Gomez-de-Regil, 2020).

OCD

Bohon, Weinbach & Lock used a computerized version of the WCST together with functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) to measure neural responses and cognitive performance of female adolescents with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). The results showed that the OCD group had a significantly greater amount of perseverative errors compared to healthy controls. With regards to neural correlates, greater activity was found in the OCD group in the inferior frontal gyrus, the right front pole, and the middle frontal gyrus when performing the Wisconsin card sort task, compared to a control matching task. This activity was not observed in healthy controls performing the WCST. The right inferior frontal gyrus is involved in inhibition. The researchers noted that the greater activity in this region in the OCD group, despite their unsuccessful performance, could suggest a greater effort to inhibit responses.

Multilingualism

The Wisconsin card sorting task can also be used in healthy populations to study cognitive skills. In a study by Czapka and Festman, the relationship between multilingualism and cognition was assessed utilizing the WCST. Since there is evidence that bilingualism can improve executive functions, the researchers wanted to see to what extent this applies to multilingual (bi- and trilingual) children by comparing their performance on the WCST and comparing it to normal monolingual controls. The researchers found that multilingual participants had significantly lower monitoring (defined as the pre-switch reaction time) scores and concluded that this supports the theory that multilingualism impacts processing speed in monitoring during the WCST.

Conclusion

The WCST is a widely known and recognized assessment tool for measuring cognitive flexibility and reasoning. While some authors point out that there may be some misunderstanding as to how to score the WCST (Miles et al., 2021) and how it is used in a clinical setting, other researchers find that the WCST is more than reliable for clinical practice and testing (Kopp, Lange, & Steinke, 2021). Furthermore, while the main cognitive function that the WCST assesses is cognitive function, given that it is a complex task, there are other processes that are bound to be involved, such as learning, memory, and attention (Miles et al., 2021). The body of research around the Wisconsin card sort task is growing to this day as it is widely used in many applications, such as studying clinical conditions like OCD or schizophrenia, but also in healthy participants to study the effects of speaking multiple languages. Overall, the test is powerful and the availability of Wisconsin Card Sort online shows its relevance for research in the 21st century.

References

- Arán Filippetti, V., Krumm, G. L., & Raimondi, W. (2020). Computerized versus manual versions of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: Implications with typically developing and ADHD children. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 9(3), 230-245.

- Berg, E. A. (1948). A simple objective technique for measuring flexibility in thinking. The Journal of general psychology, 39(1), 15-22.

- Bohon, C., Weinbach, N., & Lock, J. (2020). Performance and brain activity during the Wisconsin card sorting test in adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder and adolescents with weight-restored anorexia nervosa. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 29, 217-226.

- Chiu, E. C., & Lee, S. C. (2021). Test–retest reliability of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in people with schizophrenia. Disability and rehabilitation, 43(7), 996-1000.

- Chiu, E. C., Wu, W. C., Hung, J. W., & Tseng, Y. H. (2018). Validity of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in patients with stroke. Disability and rehabilitation, 40(16), 1967-1971.

- Czapka, S., & Festman, J. (2021). Wisconsin Card Sorting Test reveals a monitoring advantage but not a switching advantage in multilingual children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 204, 105038.

- Faustino, B., Oliveira, J., & Lopes, P. (2021). Diagnostic precision of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in assessing cognitive deficits in substance use disorders. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 28(2), 165-172.

- Gómez-de-Regil, L. (2020). Assessment of executive function in patients with traumatic brain injury with the Wisconsin card-sorting test. Brain Sciences, 10(10), 699.

- Kopp, B., Lange, F., & Steinke, A. (2021). The reliability of the Wisconsin card sorting test in clinical practice. Assessment, 28(1), 248-263.

- Miles, S., Howlett, C. A., Berryman, C., Nedeljkovic, M., Moseley, G. L., & Phillipou, A. (2021). Considerations for using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test to assess cognitive flexibility. Behavior research methods, 53(5), 2083-2091.

- Miranda, A. R., Franchetto Sierra, J., Martínez Roulet, A., Rivadero, L., Serra, S. V., & Soria, E. A. (2020). Age, education and gender effects on Wisconsin card sorting test: standardization, reliability and validity in healthy Argentinian adults. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 27(6), 807-825.