Types of Stimuli in Delay Discounting Tasks

While hypothetical money is the most common stimulus in delay discounting tasks due to its ease of manipulation and generalizability, researchers employ a wide variety of other stimuli (from food to health outcomes to entertainment and more) to investigate specific behaviors, populations, or real-world decisions.

Types of stimuli categories used in delay discounting tasks include:

- Money & Monetary Rewards

- Primary Reinforcers

Food

Drinks / Alcohol

Drugs of Abuse

Intercourse- Social Interactions

- Health Outcomes

- Environmental Outcomes

- Educational & Career Outcomes

- Consumer Goods & Experiences

These can be broadly categorized and are discussed in greater detail below.

Money and Monetary Rewards

Money is the commonly used stimuli in delay discounting tasks and is considered an effective stimulus due to several reasons. Research indicates that hypothetical money outcomes are discounted similarly to actual money outcomes, making it a practical and valid stimulus for delay discounting research. Moreover, money is not perishable or subject to satiety effects (Odum et al., 2006; Odum et al., 2020).

In delay discounting tasks using money as stimuli, participants are typically presented with a smaller immediate amount and a larger delayed amount choices and are expected to choose the two. The presented amounts vary in each trial and usually follow a pattern. For example:

- Receive $10 today or $11 tomorrow

- Receive $10 today or $50 in a month

Try out the delay discounting task or import it to your account.

Primary Reinforcers

These are stimuli that are intrinsically rewarding and often have a direct biological or physiological basis. Examples include:

Food

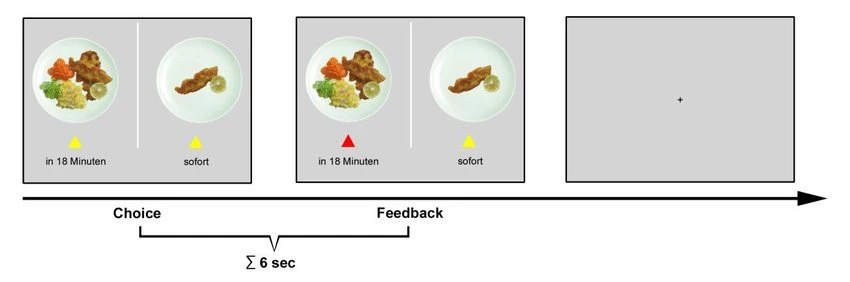

Delay discounting tasks that use food as stimuli are relevant in obesity research and are also used in studies assessing eating behavior and even animal models (e.g., a small treat now vs. a larger portion later) (Weygandt, M., et al. 2015). A study noted that food rewards are discounted more steeply than money, making them ecologically valid in obesity-related research (Rasmussen et al., 2024).

A trial progression of a food-specific delay discounting task; Weygandt, M., et al. 2015.

Drinks and Alcohol

Similar to food, stimuli of drinks are relevant for studies on thirst, alcohol use, etc. For instance, by incorporating alcohol as a reward stimulus in both single-commodity (alcohol offered now or later) and cross-commodity tasks (e.g., alcohol now vs. money later) on individuals who misuse alcohol, it was found that participants showed a stronger preference for immediate alcohol over delayed money and were more willing to wait for alcohol over immediate money (Taylor et al., 2023).

Drugs of Abuse

For individuals with substance use disorders, choices between immediate drug access (e.g., one dose now vs. three doses in two days) and delayed drug access or money can reveal very steep discounting specific to that substance. The repeated emphasis on drug-related choices highlights the impulsive nature of decision-making among drug abusers compared to non-abusers (Petry, 2003).

Intercourse

Although less common due to ethical and practical considerations, the underlying concept of immediate vs. delayed sexual gratification is relevant. In a study on sexual delay discounting, participants chose between immediate and delayed preference of sex (e.g., sex right now without protection vs. wait 3 hours for sex with protection). (Lawyer, 2008).

Social Interactions

In some delay discounting tasks, participants were presented with choices involving hypothetical face-to-face social interactions. The immediate component was speaking face-to-face right now and the delayed component was speaking face-to-face after a delay (e.g., 10 minutes speaking face-to-face with a person right now vs. 25 min speaking face-to-face with the person in 10 months) (Charlton et al., 2012).

Online Likes and Followers

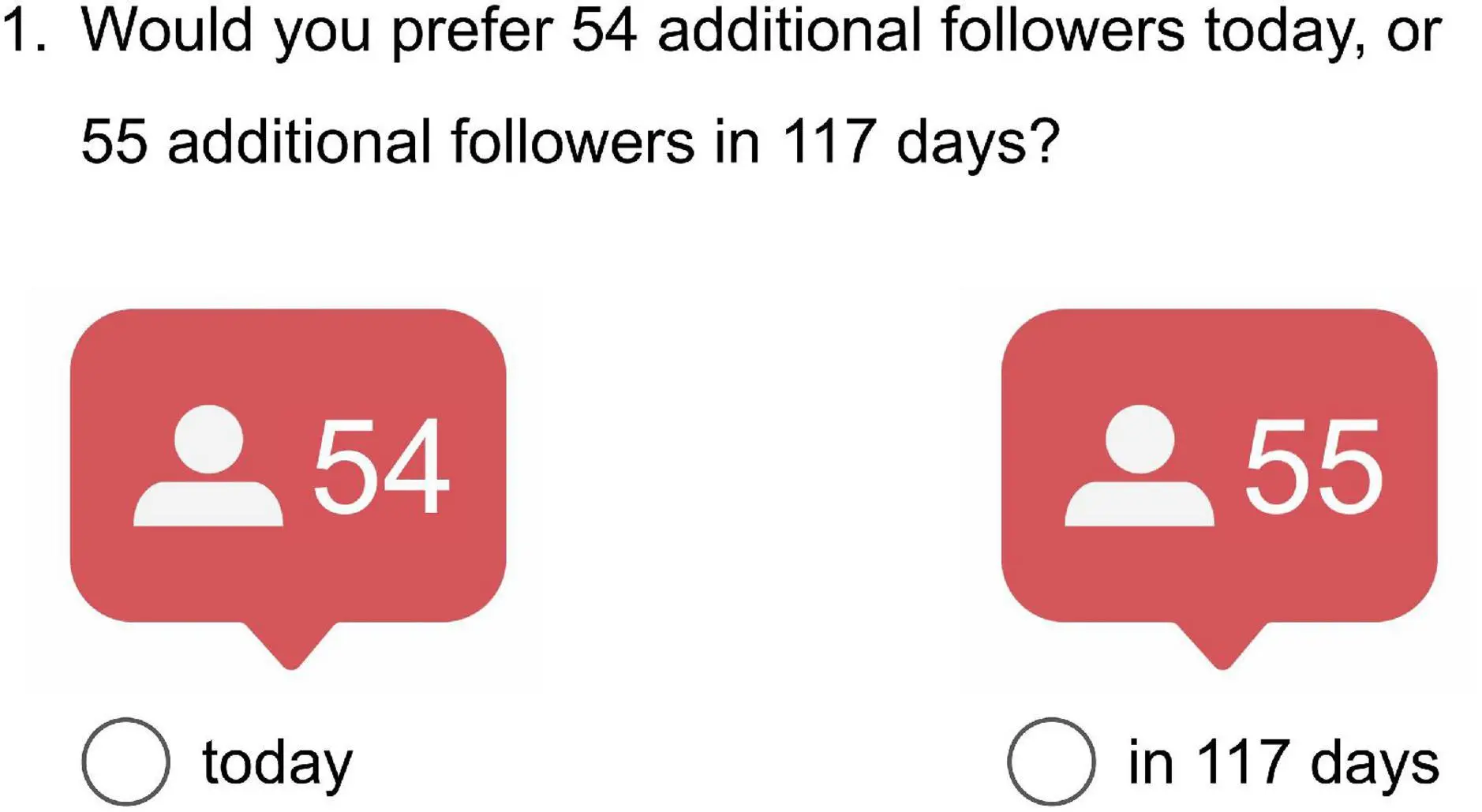

Increasingly relevant in digital contexts, is studying how participants value online-related rewards such as likes or follows.

A study used hypothetical Instagram followers and likes in a delay discounting task (e.g., a smaller number of likes or followers immediately vs. a larger number of likes or followers later on). It was found that people tend to value future Instagram followers and likes less than immediate ones, especially smaller amounts (Schulz van Endert & Mohr, 2022).

Delay discounting task for online followers; Schulz van Endert & Mohr, 2022.

Environmental Outcomes

Stimuli involving environmental outcomes have also been utilizes in order to capture decisions that involve immediate cost/effort for long-term environmental protection. The researchers could see if people were willing to pay a little now for a lot of environmental good later, or if they preferred to see the benefits sooner, even if they were smaller. For example, a smaller increase in carbon storage now (with a tax payment of ‘x’ today) vs. a significantly larger increase in carbon storage in 6 years (with a tax payment of ‘y’ in 6 years) (Grammatikopoulou et al., 2020).

Health Outcomes

These involve decisions with long-term health consequences and implications, such as medical procedures and treatment and even exercise and physical activity:

Medical Procedures and Treatment

In this context of delay discounting tasks, participants chose between immediate and delayed health scenarios.

The stimuli involved in a study were different types of health outcomes, namely, “health boost” (an immediate temporary or short-term health enhancement) and a “cure” (a delayed long-term health improvement) (Friedel et al., 2016).

Participants can be also be presented with choosing between immediate discomfort (e.g., undergoing a painful medical test now) and delayed health benefits (e.g., improved health outcomes after the test) (Talmi & Pine, 2012).

Exercise and Physical Activity

In a study using an exercise-focused delay discounting task, participants chose between exercising now or waiting for other rewards like money or food later. The results showed that exercise was valued less over time by people preferring to exercise immediately (particularly when it is self-paced) rather than delaying it for other rewards (Albelwi et al., 2019).

Educational and Career Outcomes

Delay discounting tasks can also use stimuli that revolve around education and academic achievements for youth participants, or career outcomes for older participants.

Academic Grades

This includes immediate leisure vs. future better grades. A paper focused on the qualitative aspects of delay discounting in academic contexts rather than specific time-based quantities by presenting a general concept of immediate leisure activities and inherently delayed academic tasks (e.g., “watching a television show" vs. "successfully completing and submitting an assignment") (Olsen et al., 2018).

Career Advancement

In the concepts of career, immediate comfort vs. long-term career growth are considered. Students at the end of high school were presented with the decision of immediate comfort and long-term career growth (e.g., immediate work vs. continued academic studies) (Leitão et al., 2013).

What is Labvanced?

A powerful experiment-design platform (no coding required) with advanced features like webcam eye-tracking and more via web and native desktop/mobile applications.

Consumer Goods and Experiences

Products serve as stimuli in delayed discounting tasks to study consumer preferences for immediate versus delayed gratification. For instance, in a study on consumer sales promotions, participants were presented with choices between immediate savings and delayed saving ($900 instant savings now vs. $1,000 rebate in 2 weeks) (Coker et al., 2010).

Leisure activities and entertainmnet-related stimuli can also be used to quantify choices between immediate and delayed access to experiences. For example, participants might choose between paying $500 to attend a sporting event this weekend or waiting until next month to attend for free (Goodman et al., 2019).

Conclusion

The choice of stimulus depends heavily on the research question, the population being studied, and the real-world behaviors the researchers aim to understand. Using both monetary and non-monetary stimuli in the delay discounting task can provide more ecologically valid insights into specific decision-making contexts.

References

Albelwi, T. A., Rogers, R. D., & Kubis, H. P. (2019). Exercise as a reward: Self-paced exercise perception and delay discounting in comparison with food and money. Physiology & Behavior, 199, 333–342.

Charlton, S. R., Gossett, B. D., & Charlton, V. A. (2012). Effect of delay and social distance on the perceived value of social interaction. Behavioural Processes, 89(1), 23–26.

Coker, K. K., Pillai, D., & Balasubramanian, S. K. (2010). Delay‐discounting rewards from consumer sales promotions. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 19(7), 487–495.

Friedel, J. E., DeHart, W. B., Frye, C. C., Rung, J. M., & Odum, A. L. (2016). Discounting of qualitatively different delayed health outcomes in current and never smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24(1), 18.

Goodman, J. K., Malkoc, S. A., & Rosenboim, M. (2019). The material-experiential asymmetry in discounting: When experiential purchases lead to more impatience. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(4), 671–688.

Grammatikopoulou, I., Artell, J., Hjerppe, T., & Pouta, E. (2020). A mire of discount rates: delaying conservation payment schedules in a choice experiment. Environmental and Resource Economics, 77, 615–639.

Lawyer, S. R. (2008). Probability and delay discounting of erotic stimuli. Behavioural Processes, 79, 36–42.

Leitão, M., Guedes, Á., Yamamoto, M. E., & Lopes, F. D. A. (2013). Do people adjust career choices according to socioeconomic conditions? An evolutionary analysis of future discounting. Psychology & Neuroscience, 6(3), 383.

Odum, A. L., Baumann, A. A., & Rimington, D. D. (2006). Discounting of delayed hypothetical money and food: Effects of amount. Behavioural processes, 73(3), 278-284.

Odum, A. L., Becker, R. J., Haynes, J. M., Galizio, A., Frye, C. C., Downey, H., ... & Perez, D. M. (2020). Delay discounting of different outcomes: Review and theory. Journal of the experimental analysis of behavior, 113(3), 657-679.

Olsen, R. A., Macaskill, A. C., & Hunt, M. J. (2018). A measure of delay discounting within the academic domain. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 31(4), 522–534.

Petry, N. M. (2003). Discounting of money, health, and freedom in substance abusers and controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 71(2), 133–141.

Rasmussen, E. B., Camp, L., & Lawyer, S. R. (2024). The use of nonmonetary outcomes in health-related delay discounting research: Review and recommendations. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 47(2), 523–558.

Schulz van Endert, T., & Mohr, P. N. (2022). Delay discounting of monetary and social media rewards: Magnitude and trait effects. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 822505.

Talmi, D., & Pine, A. (2012). How costs influence decision values for mixed outcomes. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 6, 146.

Taylor, H., Smith, A. P., & Yi, R. (2023). Valuation of future alcohol in cross-commodity delay discounting is associated with alcohol misuse/consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 37(1), 166.

Weygandt, M., Mai, K., Dommes, E., Ritter, K., Leupelt, V., Spranger, J., & Haynes, J. D. (2015). Impulse control in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex counteracts post-diet weight regain in obesity. Neuroimage, 109, 318-327.