The Ultimatum Game

The Ultimatum Game (UG) is a famous experiment in psychology, as well as in behavioural economics, that examines human behavior in areas such as decision-making, fairness, and morality. Since its introduction in the 1980s, it has become a widely used tool to understand these concepts. Being a simple yet effective tool, the UG has been widely utilized by researchers across the globe in fields ranging from economics to social psychology and even to clinical and comparative psychology.

Ultimatum Game: The Game Theory

Overview of the Ultimatum Game

The Ultimatum Game is a classic multi-player experiment where a fixed sum of money is split between two players. The first player (the proposer) suggested a portion that can be split while the second player (the responder) either accepts or rejects it. If the second player rejects the proposed amount from the first player, both players get nothing.

Major Uses of the Ultimatum Game

- Cognitive Processes and Emotional Responses: The Ultimatum Game helps researchers understand how emotional responses and the underlying cognitive functions of the game influence decision-making.

- Fairness and Decision Making: The game highlights how people make decisions based on the evaluation of fairness, often rejecting unfair offers, even at a personal cost.

- Behavioral Economics: The UG has a huge impact on behavioural economics by challenging the predictions of traditional economic theories.

- Social Preferences & Cultural Influences: Different societies perceive fairness, reciprocity, and punishment of unfair behavior differently. Cultural factors like laws and social norms play a significant role in shaping decision-making.

Task Details of the Ultimatum Game

The Ultimatum Game is a classic example of game theory. Game Theory is a branch of mathematics and economics that studies strategic interactions among individuals where the outcome for an individual would depend not only on their own behaviour but also on the choices of others. The ultimatum game involves two players who are tasked with splitting resources among themselves. The game operates as follows:

- PLAYER ROLES

- Proposer: The player who gets to decide on how to divide the resources and also the proportion that the responder receives.

- Responder: The player who receives the share of resources that the proposer decided on. The responder has the choice to either accept or reject the proposer’s offer.

- CONDITIONS

- Accept: If the responder accepts the proposal, the resources are divided as proposed.

- Reject: If rejected by the responder, neither the proposer nor the responder gets any resources.

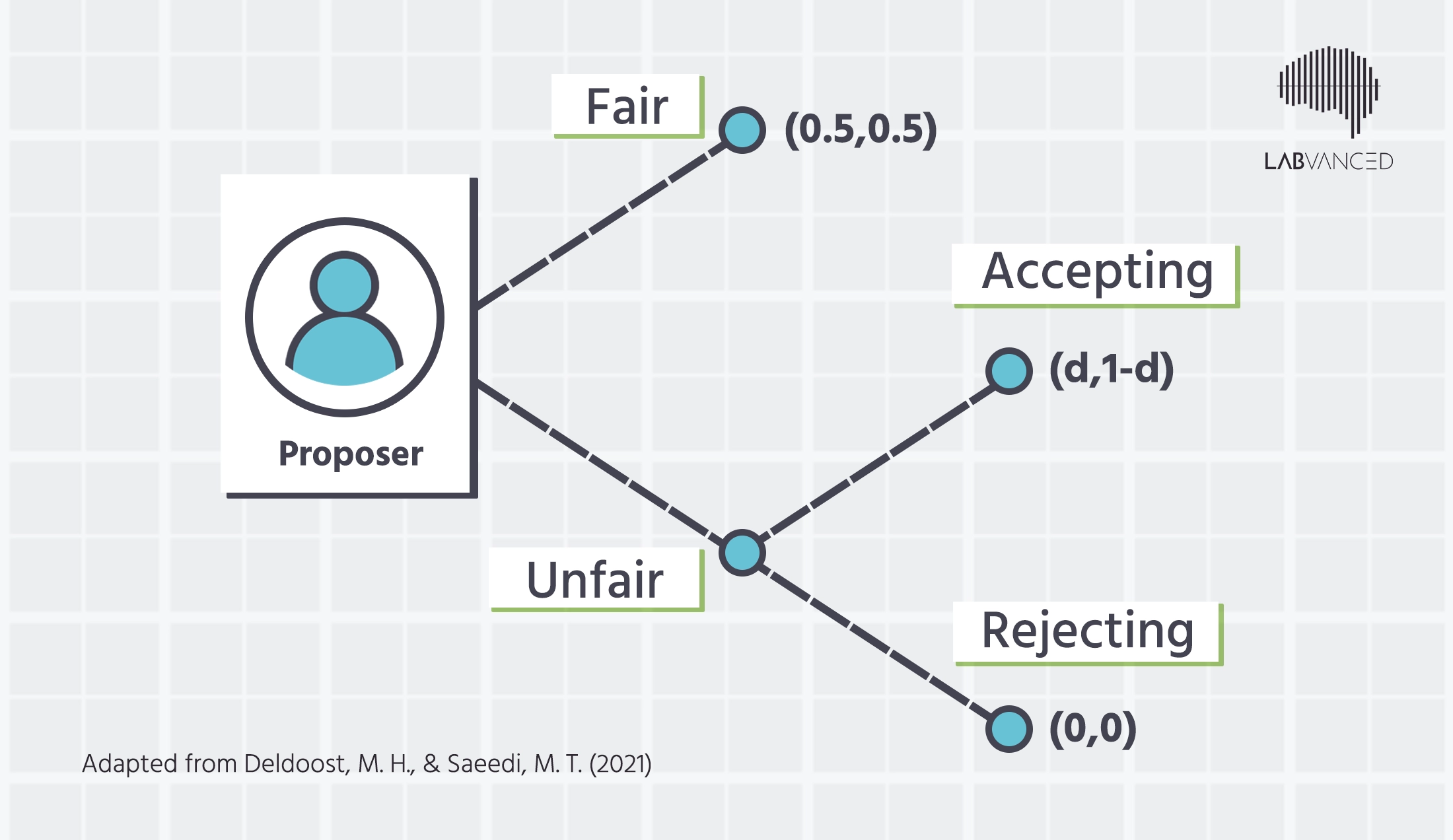

A simplified version of the Ultimatum Game; adapted from Deldoost, M.H. & Saeedi, M.T. (2021).

In a simplified version of the Ultimatum Game, the way that the proposer distributes the available sum essentially falls into two types of offers—fair and unfair.

- Fair Condition: In this scenario, both the proposer and responder receive equal proportions (d = 0.5). Here, "d" represents the proportion of the total amount allocated to the proposer. For example, if the total sum is $10, both the proposer and responder receive $5 each.

- Unfair Condition: Refers to when there is an unequal distribution of resources, with the proposer allotting more than half to themselves (1 > d > 0.5), and the responder accepts it. For example, out of the total sum of $10, the proposer may receive d=0.7 (ie $7) of the resources while the responder receives 1 - d of the resources (ie. $3).

Based on the proposer’s offer, the responder could either accept it and get the proposed amount (even if it's an unfair share). But if the responder decides to reject the unfair offer, that results in both parties receiving nothing (d = 0) (Deldoost et al., 2021). Such a setup, ie. the ability to accept an offer, gives the responder a ‘power’ here too and is the basic difference of how the Ultimatum Game is different from the Dictator Game. In the Dictator Game, the responder has no option to reject and has to accept whatever the proposer decides to share, whether they like it or not.

Demo of the Ultimatum Game in Labvanced

With regards to how offers are made, these two setups are commonly seen in the literature:

- One-shot offer: Also known as ‘single offer,’ only one offer is made per trial and the game progresses.

- Multiple offers: More advanced versions of the UG allow for multiple offers to be made in each trial. In such a setup, an offer is made and typically an outcome occurs. Based on that, learning from one trial to the next offer occurs.

Data Collected

Ultimatum game experiments collect a wide range of data in order to understand the cognitive processes underlying the game.

Some of the key metrics include the following:

- Offers: The division of money proposed by the proposer.

- Rejections: Instances where the responder rejects offers.

- Response time: The time taken by the players in making decisions.

- Eye movement data: Tracks gaze patterns, including fixation duration, fixation sequence, areas of interest, saccades, and pupil dilation.

- Additional physiological measures: Literature shows that researchers also measure physiological responses during the Ultimatum Game, such as skin conductance and heart rate (reflecting stress or excitement levels), as well as brain activity (to analyze neural responses linked to fairness and decision-making).

Possible Confounds to Consider

Several variables may influence the Ultimatum Game outcomes, requiring careful consideration while carrying out the experiment:

Emotions: Participants' emotional states, both incidental and task-related, can significantly affect and cause bias in their decision making. For instance, higher sadness has been shown to result in lower acceptance rates of unfair offers (Harlé & Sanfey, 2007).

Age: Studies have shown that age of the players could influence decision-making in the UG. Older adults are less likely to accept unfair offers. However, when presented in socially contextualized conditions (proposers presented as individuals in financial and social distress), they exhibit prosocial behaviors and accept unfair offers (Cassimiro et al., 2024).

Sense of Entitlement or Ownership: The sense of entitlement or ownership can influence the offers made by the proposers. When individuals feel that they have more rights or ownership over the amount to be shared, they tend to offer less (Matarazzo et al., 2020).

Attractiveness:

Sex/Vocal Attractiveness: Participants are more likely to accept unfair offers when they are associated with an attractive voice. Furthermore, male participants often accept unfair offers when it is associated with a female voice, regardless of attractiveness. Decision times are also longer when the voice of the proposer is attractive, regardless of whether it is from the same or opposite sex (Shang & Liu, 2023).

Facial Attractiveness: Participants are more likely to accept unfair offers from proposers with higher facial attractiveness compared to those with lower facial attractiveness. This effect is also known as the ‘beauty premium effect’ and it occurs because facial attractiveness influences decision-making through modulations in different brain regions (Pan et al., 2022).

Contextual Factors and Expectations: People’s fairness decisions depend on both what they expect and the context. If participants are told in advance what kind of offers to expect (like seeing a range or average of past offers), they adjust their idea of what is fair. Also, if the proposer is shown as being in financial trouble, participants are more likely to accept unfair offers out of sympathy (Vavra et al., 2018).

Choice Repetition Bias: A responder’s earlier decisions (whether they accepted or rejected an offer) could influence their future choices, leading them to make similar decisions again. This is often done regardless of whether it's the best choice for the current situation and could make it harder to isolate the true impact of other variables on decision-making (Chung et al., 2023).

Culture: A study aimed to understand drivers' behavior (interactions and decision-making processes) at roundabouts using the ultimatum game and found it to be a confound in the Ultimatum Game (UG). Italian drivers do not reduce speed significantly, whereas U.S. drivers tend to slow down more. This suggests that cultural factors, like laws and social norms, shape decision-making in both driving and UG.

Historical Background and Importance of the Ultimatum Game

The Ultimatum Game (UG) was first introduced by German economists Werner Güth, Rolf Schmittberger, and Bernd Schwarze in their 1982 paper titled "An Experimental Analysis of Ultimatum Bargaining." The goal of the researchers was to study how people negotiated and made decisions in a sequential bargaining setup. They designed the Ultimatum Game because it was the simplest method to study this concept. The UG utilized a simple model with minimal confusion, which was an essential factor in helping participants understand the game. The Ultimatum Game was named so because the setup reflected the proposer's position of making a take-it-or-leave-it offer, essentially presenting an ultimatum to the responder (Guala, 2008; Güth et al., 1982). Since its development, it has evolved into a widely used tool across various disciplines beyond economics, including psychology, sociology, and neuroscience.

Ultimatum Game and Economics

The Ultimatum Game has had a profound impact on the field of economics, particularly behavioral and experimental economics. Researchers designed the ultimatum game to assess how individuals balance self-interest with fairness when making decisions.

Traditional economic theories, such as the Rational Choice Theory (RCT), assume that individuals act solely out of rationality and self-interest, aiming to maximize their own gain. This would mean that proposers would offer the minimum possible amount to the respondent and the respondent would accept that offer since it is better than nothing. But, in practical experiments, the Ultimatum Game revealed that people often reject unfair offers and are willing to sacrifice personal gain to avoid perceived unfairness, with offers below one third of the available amount often being rejected. Thus, researchers have noted that the 50-50 equilibrium is an important aspect of the UG which goes contrary to the Nash equilibrium (da Silva et al., 2020.

This has challenged the predictions of traditional economic theory and the UG became a transformative tool in behavioral economics and social sciences in general. The ultimatum game is now a valuable tool that provides insights into human behavior, negotiation, reciprocity, fairness and decision making (Doğruyol et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2022).

Variations of the Ultimatum Game

Researchers have designed numerous variations of the ultimatum game over the years. Here are a few examples:

Dual-Role Method in the Ultimatum Game: This variation of the ultimatum game lets the participants play dual roles, i.e., the role of both the proposer as well as the responder. This game investigates whether the order in which participants take up these roles influences their behavior and outcomes in the game, providing a more comprehensive understanding of their preferences and decision-making processes (Macfarlan, 2010).

Emotion-Based Ultimatum Game: This variation of the ultimatum game incorporated emotional dynamics to understand how different emotional states would influence their decisions as both a proposer and a responder in the ultimatum game. Each participant was assigned one of the five basic emotions (anger, fear, joy, sadness, or surprise) and the outcomes of their interactions and negotiations were assessed (Charcon & Monteiro, 2024).

Anger-Infused version of the Ultimatum Game (AI-UG): The Anger-Infused Ultimatum Game (AI-UG) was designed to evaluate whether the UG could effectively measure irritability and anger. Participants played the AI-UG, which included elements specifically designed to provoke anger and other emotional responses. Tests assessing irritability and anger were conducted both before and after the game to measure changes in emotional states (Gröndal et al., 2024).

Spatial Evolutionary version of the Ultimatum Game: The aim of this variation is to provide researchers a means of investigating income distribution within a society, particularly focusing on the employer-employee bargaining process (Alves & Monteiro, 2019). In this variation of the ultimatum game, if the responder rejects the offer by the proposer, the money doesn’t disappear. This lets the proposer negotiate further. Also, the proposer has to get their offer accepted in order to survive in the game.

Reactive-Darwinian version of Ultimatum Game: In this advanced version of the UG, the players’ strategies for proposing distributions are the main focus. Players can adopt either greedy (G), moderate (M), or conservative (C) which differ in probability across the greed level. This set up allows researchers to study i.) the evolution of offers (ie. how the increment/decrement in the offer changes over time) and ii.) at what point their strategy changes (da Silva et al., 2020).

What is Labvanced?

Labvanced is a powerful platform designed specifically for conducting behavioral and cognitive experiments and psychological research using advanced features such as peer-reviewed eye-tracking and multi-user study support via web and native desktop/mobile applications.

Cognitive Functions Behind Ultimatum Game Theory

The Ultimatum Game, a classic example of behavioral economics and game theory, is an activity that engages multiple cognitive functions, offering insights into the interplay of mental processes. Here are the key cognitive processes:

Perception: The perception of the proposer's cognitive and emotional traits influences decision-making of the responder. Studies show that individuals are more likely to accept offers from proposers perceived as having higher agency (intelligence) and patiency (emotional capacity) (Lee et al., 2021).

Attention: Studies show that if participants allocate more attention to the proposer’s payoff, it may indicate that they are motivated by self-interest, while more attention to the responder’s payoff may reflect a preference for fairness (Wei et al., 2022).

Decision Making: Decision making is a central function in the ultimatum game. Studies suggest that the proposer’s decision making is influenced by their belief about the responder’s reservation price (the minimum acceptable offer that the responder is willing to accept). Likewise, the responder’s decision making is based on the evaluation of fairness of the offer. Such observations are in line with behavioral economics which suggest that people are not purely rational actors (van Dijk & De Dreu, 2021).

- Risk-aversion: A sub theme here is risk aversion which is the tendency to avoid risk and prefer certainty over uncertainty. Risk aversion can shape negotiation outcomes by proposers offering conservative splits to ensure acceptance, and responders accepting lower offers to avoid the risk of receiving nothing (Dilek & Yıldırım, 2023).

Cognitive Control: Cognitive control or inhibitory control helps the participants manage their emotional impulses, as studied in game theory. For example, when faced with an unfair proposal, instead of reacting based on immediate emotional responses (such as anger or frustration), cognitive control helps to reason about the long-term consequences of accepting or rejecting an offer (Wei et al., 2022).

The Ultimatum Game in Various Research Domains

The Ultimatum Game (UG) has evolved into a multidisciplinary tool, finding applications across diverse fields of research.

Below mentioned are some examples showcasing the versatility of UG's applications:

Clinical Psychology and the Ultimatum Game

The ultimatum game is a commonly utilized tool in clinical psychology research exploring conditions such as psychopathy, schizophrenia, and personality disorders, as well as broader aspects of psychopathology. A study investigated the neural responses to social interactions in individuals with major depression and/or social anxiety (MD/SA) using the Ultimatum Game. The MD/SA group reported heightened sadness in response to mid-value and unfair offers compared to controls (Nicolaisen‐Sobesky et al., 2023).

Social Psychology and the Ultimatum Game

In the context of social psychology, researchers study how game theory and ultimatum game choices are shaped by culture and social factors. In a study by Kim et al. (2024), the researchers explored how emotions, perceived reciprocity, and individual differences shape decision-making using the ultimatum game. Participants completed 30 one-shot UG trials as responders, rating expected rewards and emotions before and after offers, then deciding to accept or reject them. Findings indicated that emotions, particularly those related to reward, valence, dominance, arousal, and focus, significantly influence social decision-making (Kim et al., 2024).

Industrial Psychology and the Ultimatum Game

As mentioned previously, variations of the ultimatum game have been developed with the aim of using the game theory behind UG as a means of explaining employee-employer interactions, such as salary negotiation (Alves & Monteiro, 2019; da Silva et al., 2020)

Education and the Ultimatum Game

A study adapted the ultimatum game to make it suitable for use in classrooms. The researchers wanted to determine whether the game theory behind UG would still be observable within the context of a classroom setting and whether the UG could be leveraged as a teaching tool. It was found that the adaptations made to the game for classroom use did not change the typical outcome and kept the mechanisms behind the game theory intact. The students' understanding of how they behaved in the game provided insights into their own preferences and behaviors in relation to fairness and generosity (Bertolami et al., 2021).

Political Science and the Ultimatum Game

The Ultimatum Game was employed to investigate whether fairness or kindness in interactions could mitigate the moral derogation (moral devaluation) that people tend to have toward others with differing political views. The game was used as a tool to observe whether individuals with out-party political beliefs would still be seen as morally derogated when they engage in fair or kind actions. Findings indicated that people with opposing political beliefs are seen as less moral, and this judgment remains even with acts of fairness or kindness. Extreme partisans are especially harsh in their views (McGarry et al., 2023).

Comparative Psychology and the Ultimatum Game

The reach of the ultimatum game and game theory has even been used to assess how chimpanzees and bonobos make decisions about fairness and cooperation, by giving them access to social leverage (i.e. the power and option to access an alternative reward if they choose to reject the proposer’s offer). Findings showed that chimpanzees and bonobos made fairer offers and rejected unequal ones when responders had access to alternative rewards (Sánchez-Amaro & Rossano, 2021).

Conclusion

The Ultimatum Game stands as a powerful tool in behavioral economics and psychology research through which we can understand the complexities of human behavior. By bridging the gap between economic theory and psychological reality, the game has reshaped our understanding of social interactions. It highlights the importance of game theory and how decision making is influenced not only by rationality but also by the interplay of various factors such as emotions, perception, and sense of fairness. The diverse variations and adaptations of the game continue to expand its relevance and will remain a pivotal model for research in the years to come!

References

Alves, L. B. V., & Monteiro, L. H. A. (2019). A spatial evolutionary version of the ultimatum game as a toy model of Income Distribution. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 76, 132–137.

Bertolami, C. N., Opazo, C., & Janal, M. N. (2021). The ultimatum bargaining game: An adaptation for teaching ethics. Journal of Dental Education, 86(4), 437–442.

Bucciarelli, E., & Spallone, M. (2021). Understanding drivers’ behaviour at roundabouts: Do motorists approach a bargaining environment ‘playing’ a natural ultimatum game? Studies in Computational Intelligence, 108–117.

Cassimiro, L., Cecchini, M. A., Cipolli, G. C., & Yassuda, M. S. (2024). Age, but not education, affects social decision-making in the ultimatum game paradigm. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 82(07), 001–009.

Charcon, D. Y., & Monteiro, L. H. (2024). On playing with emotion: A spatial evolutionary variation of the ultimatum game. Entropy, 26(3), 204.

Chung, J. C., Bhatoa, R. S., Kirkpatrick, R., & Woodcock, K. A. (2023). The role of emotion regulation and choice repetition bias in the ultimatum game. Emotion, 23(4), 925–936.

da Silva, R., Valverde, P., & Lamb, L. C. (2020). A reactive-darwinian model for the ultimatum game: On the dominance of moderation in high diffusion. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 80, 104956.

Deldoost, M. H., & Saeedi, M. T. (2021). Investigating role of social value orientation in individual’s decision-making evidence from the ultimatum game. Eurasian Studies in Business and Economics, 63–74.

Dilek, S., & Yıldırım, R. (2023). Gender differences in wage negotiations: An ultimatum game experiment. İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Araştırmaları Dergisi, 12(1), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.15869/itobiad.1132446

Doğruyol, B., Yilmaz, O., & Bahçekapılı, H. G. (2020). Ultimatum game. Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior, 1–5.

Gröndal, M., Ask, K., & Winblad, S. (2024). An evaluation of the ultimatum game as a measure of irritability and anger. PLOS ONE, 19(8).

Guala, F. (2008). Paradigmatic experiments: The Ultimatum game from testing to measurement device. Philosophy of Science, 75(5), 658–669.

Güth, W., Schmittberger, R., & Schwarze, B. (1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 3(4), 367–388.

Harlé, K. M., & Sanfey, A. G. (2007). Incidental sadness biases social economic decisions in the ultimatum game. Emotion, 7(4), 876–881.

Kim, J., Bong, S. H., Yoon, D., & Jeong, B. (2024). Prosocial emotions predict individual differences in economic decision-making during ultimatum game with dynamic reciprocal contexts. Scientific Reports, 14(1).

Lakritz, C., Iceta, S., Duriez, P., Makdassi, M., Masetti, V., Davidenko, O., & Lafraire, J. (2023). Measuring implicit associations between food and body stimuli in anorexia nervosa: A go/no-go association task. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 28(1).

Lee, M., Lucas, G., & Gratch, J. (2021). Comparing mind perception in strategic exchanges: Human-agent negotiation, dictator and Ultimatum Games. Journal on Multimodal User Interfaces, 15(2), 201–214.

Leprévost, F., Grison, E., Prabhakar, A., Lhuillier, S., & Morgagni, S. (2023). From centre to suburbs: Investigating how transit maps streamline residents’ spatial representations. The Cartographic Journal, 60(4), 326–341.

Luo, L., Xu, H., Tian, X., Zhao, Y., Xiong, R., Dong, H., Li, X., Wang, Y., Luo, Y., & Feng, C. (2024). The neurocomputational mechanism underlying decision-making on unfairness to self and others. Neuroscience Bulletin, 40(10), 1471–1488.

Macfarlan, S. J. (2010). The dual-role method and ultimatum game performance. Field Methods, 23(1), 102–114.

Matarazzo, O., Pizzini, B., & Greco, C. (2020). Influences of a luck game on offers in ultimatum and dictator games: Is there a mediation of emotions? Frontiers in Psychology, 11.

McGarry, P. P., Shteynberg, G., Hulsey, T. L., & Heim, A. S. (2023). The great divide: Neither fairness nor kindness eliminates moral derogation of people with opposing political beliefs. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 15(6), 650–658.

Nicolaisen‐Sobesky, E., Paz, V., Cervantes‐Constantino, F., Fernández‐Theoduloz, G., Pérez, A., Martínez‐Montes, E., Kessel, D., Cabana, Á., & Gradin, V. B. (2023). Event‐related potentials during the ultimatum game in people with symptoms of depression and/or social anxiety. Psychophysiology, 60(9).

Pan, Y., Jin, J., Wan, Y., Wu, Y., wang, F., Xu, S., Zhu, L., Xu, J., & Rao, H. (2022). Beauty affects fairness: Facial attractiveness alters neural responses to unfairness in the ultimatum game. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 16(6), 2497–2505.

Shang, J., & Liu, C. H. (2023). The role of sex in the effect of vocal attractiveness on ultimatum game decisions. Behavioral Sciences, 13(5), 433.

Sánchez-Amaro, A., & Rossano, F. (2021). Chimpanzees and bonobos use social leverage in an ultimatum game. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 288(1962).

Trouillet, L., Bothe, R., Mani, N., & Elsner, B. (2024). Investigating the role of verbal cues on learning of tool-use actions in 18- and 24-month-olds in an online looking time experiment. Frontiers in Developmental Psychology, 2.

van Dijk, E., & De Dreu, C. K. W. (2021). Experimental Games and Social Decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 415–438.

Vavra, P., Chang, L. J., & Sanfey, A. G. (2018). Expectations in the ultimatum game: Distinct effects of mean and variance of expected offers. Frontiers in Psychology, 9.

Wei, Z.-H., Li, Q.-Y., Liang, C.-J., & Liu, H.-Z. (2022). Cognitive process underlying ultimatum game: An eye-tracking study from a dual-system perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

Zhang, P., & Zhang, S. (2024). Multimedia Enhanced Vocabulary Learning: The role of input condition and learner-related factors. System, 122, 103275